James Gifford: Edward Prime-Stevenson: Jan. 29, 1858-July 23,1942

"The first modern American gay author"

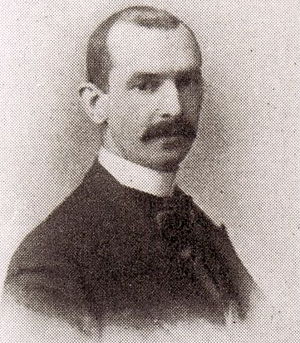

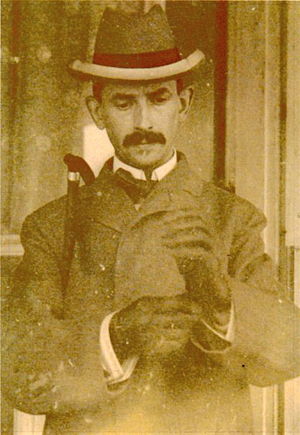

Left: Edward Irenaeus Prime-Stevenson at 40 (1898). Right: Prime-Stevenson at about 42 (ca. 1900), Hackensack, NJ. Dapper, diminutive of stature.[1]

The great gay literary critic Noel I. Garde (pseud. for Edgar Leoni) called him "the mysterious father of American homophile literature," and it would not be too strong a statement to say that he was the first modern American gay author. Yet many people do not recognize his name.

Edward Irenaeus Prime-Stevenson was born on January 29, 1858, in Madison NJ, into a wealthy and cultured family. After a private school upbringing near Freehold he claimed to have passed the New Jersey bar exam though he never practiced. His widowed mother and sister had an apartment in Manhattan and he maintained his residence at "Small House" in Hackensack, shuttling back and forth between both places until Manhattan eventually claimed him.

Stevenson established a strong niche for himself in the world of publishing, allying himself with Harpers as well as The New York Independent. He tried his hand at poetry, short fiction, magazine serials, and travel essays before he found his chief strength in music criticism. His reviews and essays were marvelously well-balanced and thought-out, always with stunning knowledge of history, and he made a modest name for himself in the music world.

Two Boys' Books

In addition, Stevenson penned two boys' books of note early in his career.

White Cockades: An Incident of the 'Forty-Five' (1887) was historical fiction, tracing a youth's infatuation with the young Prince Pretender--a feeling that is reciprocated.

Left to Themselves: Being the Ordeal of Philip and Gerald (1891) is the better book and drew more attention. In startlingly frank terms the story traces the growing affection between the eponymous heroes who meet in the opening pages. An older boy's obsession with a beautiful younger lad seemingly abandoned by his family survives the fiction's many improbable adventures, and sees them together happily "throughout their endless lives" by the end.

Such overt depiction of homosexual feelings in boys books was not unprecedented when we think of contemporary Horatio Alger productions, but while Alger's sensibilities may have been partly unconscious, Stevenson admitted later in The Intersexes that he had deliberately infused his fiction with a gay subtext that now seems quite obvious to knowing eyes.

These two works remain remarkable incursions into the genre of boys books and Philip and Gerald with its happy ending is a wonderful production that foretells Stevenson's later fiction. Many surviving copies with their presentation plates intact ironically show the admiration of church groups who apparently would give them as prizes to worthy students.

By 1900 Stevenson's mother had died (probably leaving him independently wealthy and emotionally free) and the one great affair of the 1880s-1890s, with Harry Harkness Flagler (the son of the wealthy railroad magnate), had ended badly. To what degree their feelings were mutually strong is not known, but their close friendship certainly lasted for years. When Flagler decided to marry in 1893, it was he who abandoned the heart-broken Stevenson, who would seek out Prof. George Woodberry of Columbia University for advice and consolation (see App. E in my edition of Imre: A Memorandum, Broadview Press, 2003). Haunted by this loss, Stevenson would later depict this episode in an autumnal short story "Once: But Not Twice" (1913).

Stevenson began to travel more and more frequently and eventually abandoned America altogether, leaving a distinguished career and social ties behind him for the more accepting sophistication of Europe. He gradually found himself moving from London to Paris to Budapest to Florence to Rome, and developing a regular circuit of these cities, never staying in any place past a season.

He made a modest name for himself as a lecturer in various subjects, but found most success with music "auditions" and readings of his own fiction. The Hotel Minerva in Florence, for example, hosted him throughout the 1920s. Stevenson apparently never settled down with any person in particular but became the habitue of the rented room, and roaming as he said through the highest and the lowest social circles with equal ease.

In 1905 Stevenson wrote a short piece for The Independent which charmingly describes his early stays at the Minerva. "A Little Owl of Florence" shows Stevenson at his most winsome, and probably depicts some of the feelings that were going through his head as he was beginning his nomadic life. (See Those Restless Pilgrimages, edited by Tom Sargant for Elysium Press, 2002.)

The Debut of "Xavier Mayne"

He never stopped writing, however, and in a short period after the turn of the century he wrote the two books for which he remains famous in gay literary history. Always at his own expense, and under the duress of proofing books through a non-English-speaking Italian press, Stevenson published (as Xavier Mayne) Imre: A Memorandum in 1906, followed two years later by The Intersexes: A History of Simisexualism as a Problem in Social Life. For several years Stevenson delighted in the anonymity of Xavier Mayne, and he loved to hear friends and acquaintances guess at Mayne's identity. Both books were defenses of homosexuality in a period where the medicalization of homosexuals pronounced them as nature's mistakes.

Imre

In Imre, which he called his "little psychological romance," a young Hungarian military officer meets an older man (very much like Prime-Stevenson himself) and after several misfires they eventually reveal their true natures to each other, winding up happily together. This happy ending was remarkable as the first time such a thing had happened in English-speaking fiction (it preceded Forster's Maurice by seven years). The happy conclusion is noteworthy because unprecedented: most gay writing of this period concluded with the separation or suicide of the protagonists.

The novel remains a moving recounting of the private agonies of Difference; it humanizes the homosexual image in a way that had not been done so sympathetically or thoroughly before in American writing.

Imre is heavily psychological, emphasizing character over action, so that it reads like an amalgamation of the James brothers Henry and William.

Right: Cover of German edition, 1997.[2]

The Intersexes

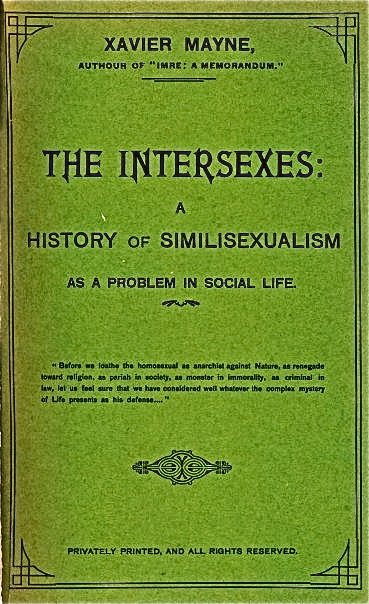

Intersexes, written at approximately the same time as Imre, is a grandly-conceived defense of homosexuality against the tyranny of dynamic psychology, which sought to pathologize gay people. Half-smilingly dedicating his work to Krafft-Ebing, Stevenson attempted a vast history of Western homosexuality from the Greeks to the present, defending its existence as part of Nature's intended canvas. He analyzes, catalogues, reveals, defends. Just as quick to see gay rogues as heroes, he outs history's famous names, good and bad, and is particularly strong in discussing literary depictions of homosexuality. Especially moving are the "modern" sections, which recount contemporary anecdotes and scandals; in doing so he paints a thoughtful and certainly indelible picture of the state of homosexuality in the first decade of the twentieth century, stunning because it is written "from the inside." Although the book was originally published in Italy with a small run of 125 copies (now each of which where found is rare and valuable), Intersexes eventually found its voice as the first great defense of homosexuality in English, all the more remarkable in that it was written by an American. Historians refer to its pages yet it is difficult to find a copy to read.

"Before we loathe the homosexual as anarchist against Nature, as renegade toward religion, as pariah in society, as monster in immorality, as criminal in law, let us feel sure that we have considered well whatever the complex mystery of Life presents as his defense...."[3]

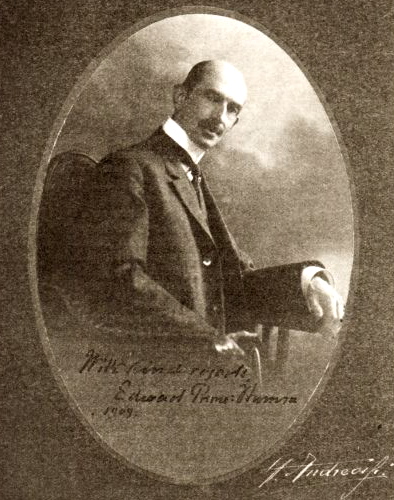

Prime-Stevenson at 51 (1909).[4]

Her Enemy, Some Friends

In 1913 Stevenson published Her Enemy, Some Friends--and Other Personages, a collection of short fiction remarkable because it included many overtly gay stories, both comic and tragic. Just as remarkable was the fact that he published the book under his own name, not as Mayne--which stands as a marker of sorts for the bravery of early gay authors in what amounts to a public outing.

Her Enemy's short stories give evidence of Stevenson's tendency to write "in accent chiefly tragic."

In "Out of the Sun" (supposedly part of a longer lost work based on the life of Baron Jacques d'Adelswärd-Fersen) gives us an unusual glimpse into the library holdings of a gay man of the period, and Dayneford's books serve as privileged markers into titles that were recognized widely by a gay underground at the time.

"The Yellow Cucumber: A Nightmare" is a comic piece deftly parodying the style of Oscar Wilde's fairy tales. In what can only be described as urban literary wit Stevenson crisply and savagely skewers what had already become gay stereotypes.

"Aquae Multae Non--" paints a picture of two men whose friendship is undone by a wicked deed only to be redeemed years later by the enduring love of the one who was wronged. Set in Bologna in 1682, this exotic period piece intertwines two of Stevenson's favorite subjects: music and homosexuality. It is worth noting that oftentimes for Stevenson, a male character's deep interest in music is often seen as a marker of sexual inversion (Imre is a major example.)

Both "Weed and Flower" and "A Great Patience" have gay subtexts, and even a "straight" story, "Madonnesca" has an in-joke with the brief appearance of the aforementioned Hungarian lieutenant Imre as a commentator on the action.

Most moving is the epistolary "Once: But Not Twice" which is a middle-aged gay man's dream of reconciliation with the love of his youth. Separated by the marriage of the younger man, his lover from years past makes a concerted effort to win him back. The story is dedicated to Harry Harkness Flagler, not surprisingly. In fact, Stevenson's many dedications--something he often provided with even his shortest productions--provide glimpses into some gay names of the past--James Gibbon Huneker, Evariste Sorrande-Lauzun, Gerard-Henri Vuerchoz, among many others. These inscriptions provide intriguing clues for future gay history research.

1920s-1930s

Stevenson stayed productive through the twenties and thirties but mostly in the field of music. Long-Haired Iopas: Old Chapters from Twenty-Five Years of Music Criticism, privately published in a limited edition in 1927, reprinted essays from his 1890s life as a critic, and he was pleasantly surprised when its modest appearance received a wider recognition from the European and American musical world than he had expected.

The 1930s found him still writing (many unpublished manuscripts were seemingly lost at his death) but growing increasingly isolated by age and the deaths of friends.

By the start of World War II Stevenson had retreated into his last hotel, the Mirabeau, in Lausanne, Switzerland, and died there on July 23, 1942. He was cremated and according to records, his ashes were given to relatives, but their resting place is unknown.

Stevenson's Age

Where his name appears, especially in library records, there remains some confusion about his age. Though birth records clearly indicate that he was born in 1858, by the time of his expatriation to Europe around 1900 he changed it to 1868 wherever he could, taking ten years off his life (while lengthening his name by adding his mother's maiden name Prime to his own family name). Although he was a short, unprepossessing man, he kept in good shape for as long as he could (the gymnasium was a special haunt) and was able to sustain this gentle lie ever afterwards. In truth, he died at age 84.

Copies of Stevenson's Works

Stevenson's work remains unfortunately hard to find. He said that many copies of his books were lost in the great earthquake at Messina in 1908, which may explain why so few of the 500 copies of Imre survive. No trace exists of an enticing work called Sebastien au Plus Bel Age, which Stevenson proudly mentions on several of his title-pages; it is thought that the entire edition may have perished in the same earthquake.

Imre and several short stories have recently been republished, and Arno Press xeroxed Imre as well as Intersexes in their famous orange-cover series years ago, but the bulk of Stevenson's extensive output remains housed in libraries and elusive to all but the most dogged pursuers.

Ironically, it is easier to find his non-gay titles in reprint, such as The Square of Sevens: An Authoritative Method of Cartomancy (1896), a bizarre hoax on fortune-telling, and Janus (1889), a foray into pulp fiction, than more important works.

Because many of his titles were only published privately in editions of 125-500 copies--each individually numbered and often signed by him--they remain true antiquarian finds. (An original Imre sold for $12,000 in 2009.) Interest in this pioneer of American gay writing continues to grow, however, and one sees that his contributions to homosexual literary history will eventually become more easily available and recognized for their importance.

References

- ↑ LEFT: Hubert, Philip G., jr. "Some of Our Music Critics." The Book Buyer 18.4 (May 1899): 303-307. Print. RIGHT: Photo courtesy coll. Tom Sargant.

- ↑ Wolfram Setz's German edition of "Imre". Männerschwarm, 1997. Kartoniert/Broschiert. Reprinted from "Imre. Ein Erlebnis. Aus dem Englishen von D.G.", ca. 1910.

- ↑ Epigraph from the cover and title page of The Intersexes. Original green wrapper, courtesy coll. Raimondo Biffi.

- ↑ Picture from The Musical Courier (12 Jan. 1910), courtesy Sibley Music Library, Eastman School of Music, U of Rochester NY.

Bibliography

Austen, Roger. Playing the Game: The Homosexual Novel in America. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1977.

Bergman, David. Gaiety Transfigured: Gay Self-Representation in American Literature. Madison: U of Wisconsin P, 1991.

Féray, Jean-Claude, ed. Du simisexualisme dans les Armées et de la prostitution homosexuelle (militaire et civile) a la Belle Epoque. Exc. The Intersexes by E.I. Prime-Stevenson. Paris: Quintes-Feuilles, 2003.

---, and James Gifford. "Ein 'Komparatist' uber Homosexualitat in Europa." In: Forum Homosexualitat und Literatur 42 (2003): 37-51.

---, and Raimondo Biffi. "Xavier Mayne (Edward I. Prime-Stevenson), Romancier Français?" Inverses: Littératures, Arts, Homosexualités I (2001): 47-57.

Fone, Byrne R.S. A Road to Stonewall: Male Homosexuality and Homophobia in English and American Literature, 1750-1969. New York: Twayne, 1995.

Garde, Noel I. (Edgar Leoni). "The First Native American 'Gay' Novel," One Institute Quarterly of Homophile Studies 9 (Spring 1960): 185-190.

---. "The Mysterious Father of American Homophile Literature," One Institute Quarterly of Homophile Studies 3 (Fall 1958): 94-98.

Gifford, James. Dayneford's Library: American Homosexual Writing 1900-1913. Amherst: U of Massachusetts P, 1995.

---, ed. Glances Backward: An Anthology of American Homosexual Writing, 1830-1920. Peterborough: Broadview, 2007.

---, ed. Imre: A Memorandum 1906. By Edward Prime-Stevenson. Peterborough: Broadview, 2003.

---. "Left to Themselves: The Subversive Boys Books of Edward Prime-Stevenson." Journal of American and Comparative Cultures 24.3/4 (Fall/Winter 2001): 113-116.

Hafkamp, Hans, ed. Imre: een memorandum, by Xavier Mayne (Edward Prime-Stevenson). In: Gay 2000, Een jaarboek samengesteld door. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Vassallucci, 1999. 121-240.

Herzer, Manfred. "'The Very Rubbish of Humanity'--Prime-Stevenson und der Schwulen Kitsch in der Literatur am Beginn des zwanzwigsten Jahrbunderts." Capri. Zeitschrift fur schwule Geschichte 32 (2002): 10-14.

Hubert, Philip G., Jr. "Some of Our Music Critics." The Book Buyer 18.4 (May 1899): 303-307.

Livesey, Matthew Jerald. "From This Moment On: The Homosexual Origins of the Gay Novel in America." Diss. U of Wisconsin, Madison, 1997.

Miller, Philip Lieson. "Edward Prime-Stevenson: Expatriate Opera Critic." The Opera Quarterly 6 (Autumn 1988). 37-51.

Mitchell, Mark, and David Leavitt, eds. Pages Passed from Hand to Hand: The Hidden Tradition of Homosexual Literature in English from 1748 to 1914. Boston: Mariner, 1997.

Sargant, Tom, ed. Mystically My Heart: Two Poems by Edward Prime-Stevenson. Pomfret VT: The Scoundrel Press, 2004.

---, ed. Those Restless Pilgrimages. Pomfret VT: Elysium Press, 2002.

Setz, Wolfram. Afterword: "Ein literarischer Fall" [A Literary Case]. Imre: Eine Psychologische Romanze. By Xavier Mayne (Edward Irenaeus Prime-Stevenson). Trans. D.G. Ed. Wolfram Setz. Berlin: Bibliothek rosa Winkel, 1997. 143-160.

Stevenson was a prolific correspondent, and letters to relatives and friends reside in various collections, such as the Bibliotheque Cantonale et Univeritaire (Lausanne), the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin, Houghton Library (Harvard University), Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library (Yale University), and Princeton University Library, as well as in private collections.

<comments />