Jonathan Ned Katz, Recalling My Play "Coming Out!" June 1972

"one of the most . . . profound communal experiences of my life"

Early in childhood, in anxious exile from hurtful intimacies, I became a loner in the crowd, working assertively to gain accolades from grownups by producing colorful, primitive tempera paintings, all the while surrounded by a protective, isolating cocoon.

And in the private, progressive Greenwich Village elementary school, The Little Red School House, I moved aggressively among my classmates, bidding for their attention by putting out a newsletter, Jon’s Journal, and hanging out with the A-list clique, all the while surrounded by an invisible, isolating wall.

As an art major at Music and Art, a public high school, among a class of 300 artists and musicians, I received plaudits for my paintings, was elected Features Editor of the school paper, and directed my class’s varsity show, all the while remaining completely separate and alone, aloof from close relationships, firmly encased in my own private isolation booth.

Only after a first sexual encounter with a classmate, a male, at age 18, in 1956, did I begin to feel the need to reach out. Only then did I begin to yearn for human contact. And only then did I begin to feel searingly, achingly lonely. But, fearing intimacy and hurt, and inexperienced in the ways of making connection, I was often alone.

In the 1960s, I began individual psychotherapy with a humane heterosexual, Herb Freudenberger, who had escaped Nazi Germany on his own as a young child and, amazingly, made it alone to the U.S. It came as quite a shock when, a year or so into therapy Herb rejected what had been my opening complaint: “Your problem isn’t homosexuality, it’s that you don’t relate to anybody!”

The shock subsided and I began slowly to venture out of my shell, helped especially by the experience of Herb’s group sessions. I began to feel better about myself and my ability to sustain relationships and even the hurts they sometimes bring. In the early 1970s, with fear and trembling, I began to explore New York City’s recently founded gay liberation groups.

Rarely in our lives is there an actual, solid, heavy, wooden door (not a metaphorical door) that we know, if we have the guts to open it and walk through it, will utterly change the rest of our lives for the better, but in ways we can’t imagine.

As I approached the door of the Episcopal Church on 28th Street and 9th Avenue in New York City, where the Gay Activists Alliance was holding weekly meetings, one evening in the winter of 1971, I knew that crossing that threshold would change my life. I took a deep, anxious breath and walked in.

At the age of thirty-three I began attending the raucous weekly meetings of the GAA, and the eloquent oratory of the group’s leaders rang in my ears. (“We're demonstrating for our lives!” exclaimed Arnie Kantrowitz in one impassioned speech. Arthur Evans, Jim Owles, Marty Robinson, and Vito Russo also gave eloquent speeches.) I saw the world with fresh eyes. I participated in public actions and took part in intense private discussion groups and psychologically probing “consciousness-raising groups.” I marched with a poster that proclaimed: “Homosexuals are revolting. You bet we are!”

In a few short months I weathered a destabilizing change. I came home from those wildly exhilarating meetings exhausted, my head literally spinning from the intense, abrupt shift in understanding and emotion I was so quickly undergoing.

I experienced a fundamental mental alteration, from a sense of myself as individual monster-freak to a new, shared sense of myself as member of a put-down group, newly outraged, organized, resistant, and public. In the gay movement I affirmed my affectionate and erotic feelings for men, the particular emotions for which society put me down, and for which, for so many years, I put myself down.

My participation in the gay movement soon led to my first imagining such a thing as homosexual history. At a meeting of the Gay Activist Alliances’ Culture Committee, in the apartment of Alan Jay Glueckman on 15th Street, in then-unfashionable Chelsea, we talked of ways to publicize our new movement. I then privately resolved to research and compile a documentary theater piece on gay and lesbian life and liberation.

Like Martin Duberman’s documentary play In White America, which I’d heard about but not seen, the piece I imagined would employ American historical and literary materials to evoke dramatically our changing situation, emotions, and consciousness.

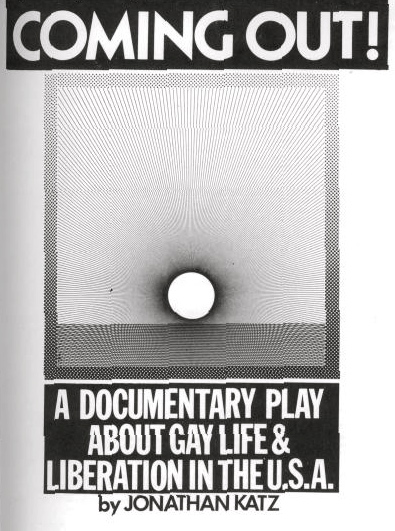

The agitation-propaganda theater piece, Coming Out!, produced by the Gay Activists Alliance Arts Committee, opened on June 16, 1972, at GAA's rented firehouse, reproduced in September 1972 at the Washington Square Methodist Church, and then again in June 1973 at The Nighthouse, in a tiny theater (a ground-floor room, actually), in Chelsea.

Martin Duberman’s comments on that last production, on the front page of The New York Times Sunday drama section, encouraged a publisher to give me a contract for a book of documents on homosexual history ($2,500 on signing, $2,500 three years later on the manuscript’s acceptance), and my book Gay American History: Lesbians and Gay Men in the U.S.A. was published at the end of 1976.

Given my earlier history as anxious, isolated, lonely loner, the six months we spent developing and rehearsing Coming Out!, from January to June, 1972, was one of the most exciting, challenging, and profound communal experiences of my life.

I attended every rehearsal of the piece, and my interactions with the director, David Roggensack, stage manager, Reed Lenti, and the actors included creative challenges: how to make the words of my documentary compilation come alive on stage; how to wrest honest, heartfelt readings out of non-professional actors (a couple of professional actors started rehearsals but then dropped out, concerned that their participation in a gay liberation play would negatively effect their future theatrical careers).

The challenges also included confronting tensions between the militant lesbian feminists in the cast and the not-so-feminist gay men, the alcohol consumption of one participant, and almost everybody’s anxieties about using their real names in the publicity for a gay liberation play.

Indeed, still deep in the closet, on the first version of the script I had used the pseudonym “Jon Swift,” though it soon dawned on me that a pseudonym just wouldn’t do on a theater piece titled Coming Out! (exclamation mark). So, along with the other participants in what felt like a daring, scary venture, I gulped and said “OK, use my real name.” Sure enough, at 10 a.m. on the Friday morning of the play’s opening my telephone rang and it was my mother. Her voice quavered, she was on the verge of tears, and she’d seen an ad for Coming Out! “Is that you in The Village Voice?” “Yes,” I answered.” “Are you a . . . a homo-sexual?” “Yes.” “Why didn’t you tell me?” “Because I knew you’d react like you’re reacting.” “But why do you have to be so public?” “Because I have to.”

So the play Coming Out! included my own coming out to my mother and, after several years, the start of a new relationship between us. Over these years she moved from knee-jerk anti-homosexual hysteria to using her editing skills (honed as a long-time Associate Editor at Parents’ Magazine) to help me edit the book that became Gay American History. Mother love triumphed over homophobia.

My work on the play Coming Out! initiated my new life as an open gay person, my long professional career as a historian of sexuality and gender, and furthered my movement into the world of human relationships, with all their pleasures and, of course, their pains. My work on Coming Out! helped make me human.