Jonathan Ned Katz: "Comrades and Lovers," Act II, Part II

From OutHistory

Jump to navigationJump to searchContinued from: Jonathan Ned Katz: "Comrades and Lovers," Act II

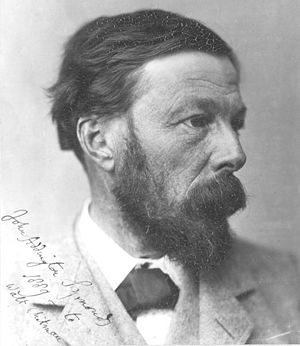

- SCENE TITLE: 7 Horace Traubel, "Whitman asked me"

- HORACE TRAUBEL, GAZING AT STAFFORD AND WHITMAN, HEARS WHITMAN'S LAST LINES. TRAUBEL INTRODUCES HIMSELF TO AUDIENCE

TRAUBEL:

- Horace Traubel.

- Whitman asked me

- about last night's meeting,

- which sat till after 12

- in Philadelphia

- about a dozen men present.

- "Calamus" had been much discussed --

- Sulzberger questioning the comradeship

- there announced

- as verging upon

- the licentiousness of the Greek.

- Whitman took it very seriously:

WHITMAN:

- 70-YEARS-OLD

- He meant the handsome Greek youth

- one for the other?

- I can see how

- it might be opened

- to such an interpretation.

- But in the ten thousand

- who for many years

- have stood ready

- to make any possible charge against me,

- none has raised this objection.

- "Calamus" is to me indispensable--

- LIGHTS UP ON JOHN ADDINGTON SYMONDS WHO, HEARING WORD "CALAMUS, STANDS UP, LOOKING AT WHITMAN WITH GREAT ANTICIPATION

- not there alone

- in that one series of poems,

- but in all.

- It could no more be dispensed with

- than the ship entire.

- SYMONDS MOVES FRONT. TWENTY YEARS AFTER HIS INITIAL INQUIRY ABOUT WHITMAN, HE IS STILL HOTLY PURSUING HIS QUESTIONS ABOUT WHITMAN'S CALAMUS THEME

- SCENE TITLE: 8 John Addington Symonds, "In your conception of Comradeship"

- SYMONDS SPEAKS DIRECTLY AND INTENSELY TO WHITMAN, READY, FINALLY, FOR A SHOWDOWN WITH WHITMAN ON THE SUBJECT OF SEX IN THE INTIMACIES OF MEN WITH MEN

SYMONDS:

- In your conception of Comradeship,

- do you contemplate

- the possible intrusion

- of those semi-sexual

- emotions and actions

- which do occur

- between men?

- I do not ask

- whether you approve of them,

- or regard them

- as a necessary part of the relation.

- But I should much like to know

- whether you are prepared

- to leave them

- to the inclinations

- and the conscience

- of the individuals concerned?

- For my part,

- I hold that the present laws

- of France and Italy

- are right.

- They protect minors,

- punish violence,

- and guard against

- outrages of public decency.

- They leave individuals

- to do what they think fit.

- These principles

- are in open contradiction

- with English and American legislation.

- It has frequently occurred to me

- to hear your "Calamus" poems

- objected to

- as praising

- and propagating

- a passionate affection

- between men

- which might "bring people into criminality."

- I agree that some men,

- having a strong natural bias

- toward persons of their own sex,

- the enthusiasm of your "Calamus" poems

- is calculated to encourage

- ardent and physical intimacies.

- I do not agree

- that such a result

- would be absolutely prejudicial

- to social interests.

SPEAKER 1:

- REPEATING WHITMAN'S EARLIER WORDS

- I do not press my finger across my mouth.

SPEAKER 2:

- REPEATING WHITMAN'S EARLIER WORDS

- I am for those who believe in loose delights

SPEAKER 3:

- REPEATING WHITMAN'S EARLIER WORDS

- All themes stagnate in their vitals,

- if they cannot publicly accept

- and publicly name,

- with specific words,

- those things on which

- all that is worth being here for depend.

SPEAKER 4:

- REPEATING WHITMAN'S EARLIER WORDS

- It is to the development

- of that fervid comradeship,

- the adhesive love

- of man and man,

- that I look

- for the counterbalance

- of our materialistic,

- vulgar

- American democracy.

WHITMAN:

- SPEAKING DIRECTLY TO SYMONDS

- Your questions

- about my Calamus pieces

- quite daze me.

- That the Calamus part

- has opened --

- even allowed --

- the possibility

- of such construction as mentioned

- is terrible.

- I am fain to hope

- that the pages themselves

- are not to be even blamed --

- mentioned --

- for such gratuitous

- and quite

- at the time

- undreamed

- and unreckoned

- possibility

- of morbid inferences --

- which are disavowed by me

- and seem damnable.

- My life,

- young manhood, mid-age

- have all been jolly

- and probably open to criticism.

- Though always unmarried

- I have had six children.

- IMMEDIATELY, WHITMAN'S SIX "SONS" APPEAR AROUND HIM: PETER DOYLE, THOMAS SAWYER, LEWIS BROWN, DOUGLASS FOX, HARRY STAFFORD, EDWARD CATTELL.

- THEN SYMONDS RESPONDS TO WHITMAN, WITH A NOTE OF DISBELIEF AND IRONY

SYMONDS:

- I am sincerely obliged to you

- to know

- so precisely

- that the "adhesiveness" of comradeship has no interblending

- with the "amativeness" of sexual love.

- SYMONDS TURNS AWAY FROM WHITMAN TO SPEAK TO EDWARD CARPENTER

- Whitman did not quite trust me perhaps.

- Afraid of being used

- to lend his influence

- to "Sods."

CARPENTER:

- TO SYMONDS

- Personally,

- having known Whitman fairly intimately,

- I do not lay great stress on that letter.

- Whitman was

- in his real disposition

- the most candid,

- but also

- the most cautious of men.

- TO AUDIENCE

- An attempt was made

- on this occasion

- to drive him

- into some sort of confession

- of his real nature;

- that very effort

- aroused all his resistance

- and caused him to hedge

- more than ever.

- TO SYMONDS

- If Whitman took

- the reasonable line

- and said that,

- while not advocating

- abnormal relations

- in any way,

- he of course

- made allowance

- for possibilities in that direction

- and the occasional development

- of such relations,

- why, he knew

- that the moment he said such a thing

- he would have

- the whole American press at his heels,

- snarling and slandering.

- TO AUDIENCE

- Things are pretty bad here in England,

- but in the states

- (in such matters)

- they are ten times worse.

- SCENE TITLE: 9 Gavin Arthur, "In spite of his 80 years"

ARTHUR:

- ADDRESSING THE AUDIENCE AS A CLOSE FRIEND

- In spite of his 80 years,

- Edward Carpenter's eyes

- were a vivid sky-blue;

- his face was copper,

- his hair shining silver.

- TO CARPENTER

- I was twenty-two.

CARPENTER:

- Welcome, my boy!

- HE EMBRACES ARTHUR, HOLDING THE HANDSOME YOUTH ONE SECOND TOO LONG, KISSING HIM WARMLY ON BOTH CHEEKS

ARTHUR:

- TO AUDIENCE

- He smelled like leaves

- in an autumn forrest.

- A sort of seminal smell.

- CARPENTER MIMES INTRODUCTIONS

- He introduced me

- to his comrade George

- and George's comrade Ted.

- We talked about Walt.

- Carpenter said

CARPENTER:

- Walt would have loved you

ARTHUR;

- the others agreed

- and my heart beat hard.

- After supper Ted suggested

- a walk in the moonlight.

- ARTHUR AND TED WALK OUT TOGETHER

- We talked about Carpenter.

- Then Ted said:

TED:

- Why don't you spend the night?

- It would do Eddy so much good

- to sleep with

- a good looking young American.

ARTHUR:

- I would like nothing better,

- I said.

- We approached the fire,

- before which the Old Man was sitting.

- Ted looked down at him lovingly:

TED:

- Gavin wants to sleep with you tonight, Eddie.

- Ain't you the lucky old dog?

ARTHUR:

- The other two went up to bed.

- The old man and I sat by the fire.

- We talked again of Walt.

- I blurted out,

- half afraid to ask:

- "I suppose you slept with him?"

CARPENTER:

- Oh yes --

- he regarded it

- as the best way

- to get together with another man.

- He thought

- people should know each other

- on the physical and emotional plane

- as well as the mental.

- The best part of comrade love

- was that there was no limit

- to the number of comrades one could have.

ARTHUR:

- "How did he make love?"

- I forced myself to ask.

CARPENTER:

- I will show you.

- ARTHUR SITS STAGE CENTER; CARPENTER IN BACK OF ARTHUR, HOLDING HIM; WHITMAN SITS IN BACK OF CARPENTER. NO SEXUAL ACTIVITY NEEDS TO BE PORTRAYED, THE WORDS ARE POWERFUL ENOUGH

ARTHUR:

- We were both naked.

- We lay side by side

- on our backs

- holding hands.

- Then he was holding my head

- in his two hands,

- making little growly noises,

- staring at me in the moonlight.

- "This is the laying on of hands,"

- I thought.

- "Walt.

- Then Edward.

- Then Me."

- The old man at my side

- was stroking my body

- with the most expert touch.

- I lay there in the moonlight pouring in at the window,

- giving myself up

- to the loving old man's marvelous petting.

- Every now and then

- he would bury his face

- in the hair of my chest,

- agitate a nipple

- with the end of his tongue,

- or breathe in deeply from my armpit.

- I had of course a throbbing erection

- but he ignored it

- for a long time.

- Very gradually, however,

- he got nearer and nearer,

- first with his hand

- and later with his tongue

- which was now

- flickering all over me

- like summer lightning.

- I stroked whatever part of him

- came within reach of my hand

- but felt instinctively

- this was a one-sided affair,

- he being so old

- and I so young,

- and that he enjoyed petting me

- as much as I enjoyed being petted.

- At last his hand

- was moving between my legs

- and his tongue

- was in my bellybutton.

- Then he was tickling my fundament

- just behind the balls

- and I could not hold it any longer,

- his mouth closed over the head of my penis

- and I could feel my young vitality

- flowing into his old age.

- He did not waste that life-giving fluid.

- As he said afterward:

CARPENTER:

- LECTURING A BIT, EVER THE TEACHER

- It isn't the chemical ingredients

- which are so full of vitality

- it's the electric content,

- like you get in milk

- if you drink it

- direct from the cow --

- so different from cold milk!

ARTHUR:

- I fell asleep

- like a child

- safe in father-mother arms,

- the arms of God.

- SPEAKING OF RELIGION; LIGHTING/MOOD CHANGE]

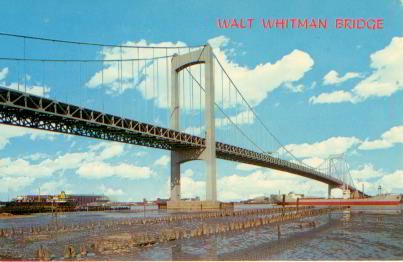

- SCENE TITLE: 10 The New York Times, December 17, 1955

SPEAKER 1:

- Roman Catholics of the Camden diocese

- opened a campaign today

- to prevent the naming

- of a new Delaware River bridge

- after Walt Whitman.

SPEAKER 2:

- When asked

- why Whitman was objectionable,

- the Reverend Edward Lucitt,

- director of the Holy Name Society,

- cited a recent biography of Whitman

- by Dr. Gay Wilson Allen

- who had called the poet

ALLEN:

- a "homo-erotic."

SPEAKER 3:

- But Dr. Allen said last night

- that he had no intention

- of implying that Whitman

- was a homosexual:

ALLEN:

- I used the term "homo-erotic"

- rather than "homosexual"

- because homosexual

- suggests sex perversion.

- There is absolutely no evidence

- that Whitman engaged

- in any perverted practice.

- Whitman's writings show

- a strong affection for men.

- Many saints

- show the same feeling.

SPEAKER 4:

- Children of fifty-eight parochial schools

- in the Camden diocese

- are being asked

- to submit essays

- on "great men of New Jersey"

- in the hope

- of inspiring another name

- for the bridge.

- LIGHTING/MOOD CHANGE. PETER DOYLE TO FRONT CENTER OF STAGE

- TITLE: 11 Peter Doyle, "I have Walt's raglan here"

- DOYLE SPEAKS TO THE AUDIENCE AS A GOOD FRIEND. HERE, DOYLE IS ABOUT 50

DOYLE:

- I have Walt's raglan here.

- PUTS THE OVERCOAT ON

- I now and then put it on,

- lay down,

- think I am in the old times.

- Then he is with me again.

- It's the only thing I kept

- amongst many old things.

- When I get it on

- and stretched out on the old sofa

- I am very well contented.

- It is like Aladdin's lamp.

- I do not ever for a minute

- lose the old man.

- He is always near by.

- When I am in trouble --

- in a crisis --

- I ask myself

- "What would Walt have done

- under these circumstances?"

- and whatever I decide

- Walt would have done

- that I do.

- Towards the end

- he continued to write to me.

- He never altered his manner toward me;

- here are a few postal cards,

- HOLD UP POSTCARDS

- you will see

- they show the same old love.

- He understood me --

- I understood him.

- We loved each other deeply.

- Walt realized

- I never swerved from him.

- But I have talked a long while.

- Let us drink this beer together.

- HOLDS UP A BOTTLE

- It's a fearful warm day.

- You take the glasses, there;

- Now, here's to the dear old man

- and the dear old times --

- and the new times, too,

- and everyone that's to come!

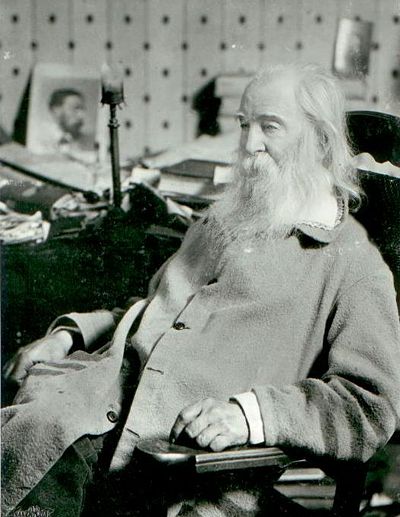

- TITLE: 12 Walt Whitman, "No labor-saving machine"

- WHITMAN SPEAKS TO AUDIENCE AS COMRADE AND LOVER

WHITMAN:

- No labor-saving machine, Nor discovery have I made,

- Nor will I be able to leave behind me any wealthy bequest to found a hospital or library,

- Nor reminiscence of any deed of courage for America,

- Nor literary success nor intellect, Nor book for the bookshelf,

- But a few carols vibrating through the air I leave,

- For comrades and lovers.

- BLACKOUT