Jonathan Ned Katz: Rediscovering Lucien Price, November 7, 1988

Republished from The Advocate, November 7, 1988, copyright by Jonathan Ned Katz.[1]

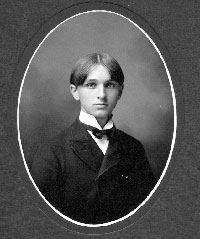

Lucien Price, graduate in 1901 from the Western Reserve Academy, Hudson, Ohio.[2]

In 1919, Boston journalist Lucien Price began to write what would become an eight-volume series of novels on a homosexual emancipation theme.

Between 1951 and 1962, Price privately published seven of these novels, each of which tells a self-contained story, with the whole covering the years 1893 to the late 1950s--historical fiction providing a panoramic view of American male homosexual life and including many autobiographical details.

Printed in small editions of several hundred copies, Price's novels have remained unknown, their author forgotten. [In 1988, I said that the "novels are mentioned in only one obscure published source".]

Price and his novels were brought to my attention by an extremely generous correspondent, Michael Dunn, who volunteered to research Price's life, read all his novels, and then sent me an extraordinary 106-page report.

I later bought six of Price's novels, two signed by the author and dedicated to he Kinsey Institute, to which he had sent them. I paid a bookseller about $8 each for Price's books after they were de-accessioned (as they say) by the Kinsey library, which obviously had no idea what it was selling. (So much for the safety of our treasures in major archives.)

Price collectively titled his novels All Souls, a reference to All Souls' Day, the Christian festival in remembrance of the dead. The day was associated for Price with the death and continuing creative influence of Fred Demmler, a young friend (possibly a lover) killed on All Souls' Day, 1918, days before the end of World War I--a death motivating Price to start his novels.

The title All Souls also referred to the rebirth of ancient Greek homosexual love in the modern world as a creative, civilizing force.

As documents of homosexual history and resistance, Price's novels are a fascinating, valuable discovery. As literature, I'm afraid, Price's fictions are fatally flawed. Their plots are melodramatic; their characters, idealized. In these novels, all homosexuals are wise, good, beautiful, and creative; Price's neo-Greek aristocrats always dress for dinner, never splashing spaghetti sauce over their starched white shirtfronts.

Price's purple plots are suggested by a summary of his series's third novel, The Sacred Legion: The Lion of Charonaea. This picks up the story of poet and playwright Ross MacNeil and sculptor Dion Diomedes who, with their great-grand-daddy's lost gold (recovered fortuitously in an earlier volume), move to Lesbos in Greece (yes, Lesbos). They buy a half-ruined old monastery, and when an earthquake cracks the foundations of this Christian edifice (get the symbolism?), the two discover the entrance to an ancient tomb. In it are several old Greek papyruses, the texts, no less, of three lost ancient Greek homosexual plays, and the complete poems of Sappho!

Convinced that heterosexual society would rather destroy these documents than admit their existence, the two arrange to smuggle them out of Greece with the help of a woman friend (who may have had a special interest in Sappho). In America, their friends secretly prepare to reveal the lost poems and plays to the world, forcing it to recognize the existence of an old, valuable homosexual love. Price's novels now read as rather plodding camp liberation classics.

Much more interesting to us than Price's novels would be a book about his life, the details of which are now known only in outline.

He was born in 1893 in Kent, Ohio. His father was a doctor. Price attended Harvard from 1903 to 1907, graduating with honors. There he became lovers with Fred Middleton, another student, with whom he remained friends for life, though Middleton's marriage interrupted their "David-Jonathan friendship" (as Price's early memorialist put it).

From 1907 to 1914 Price worked as a reporter and music reviewer for the Boston Transcript. In 1912 he picked up Fred Demmler in a Boston working-class restaurant and fell in love with the athletic 24-year-old artist.

The famous textile workers' strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1912, made Price aware of the desperate conditions of the town's mill workers and constituted an important moment in his political development. Having sent Price to cover the strike, the Transcript refused to publish his reports because they were too sympathetic to the workers.

In 1914 Price, radicalized by the Lawrence strike, began publishing, under the name Seymour Deming, critiques of American society inspired by the Fabian socialism of G. B. Shaw and H. G. Wells. Price spoke with respect of the Industrial Workers of the World, syndicalists, muckrakers, European social democrats, and militant suffragists.

From 1914 to 1964, the year of his death, Price wrote editorials for the Boston Globe. Among Price's friends were historian Samuel Eliot Morison, philosopher Alfred North Whitehead, and modern dance pioneer Ted Shawn (who called Price "the greatest man I have ever known"). Gore Vidal dedicated a novel, Julian, to Price.

Price's papers at Harvard, including I70-or-so notebooks and his correspondence, open to researchers since 1984, could also, no doubt, tell us much of interest about this unknown homosexual emanancipation pioneer.

Gore Vidal Comments on Lucien Price

When preparing the above essay, Jonathan Ned Katz wrote to Gore Vidal, asking him to comment briefly on Lucien Price. Vidal responded that he met Price after he had publicly praised Vidal's novel Messiah (1975) in the Boston Globe. "This was a time when I was either not reviewed or strongly attacked. I got to know him during the decade (his last) when I could no longer publish novels [and] had turned to theater, TV. . . ."

Vidal recently explained in The New York Review of Books that after publishing The City and The Pillar (1948), "about the love affair of two ordinary American youths," his next five novels were not reviewed in The New York Times, Time, or Newsweek, and he was forced to turn away from novel writing for ten years. With Julian (1964), Vidal dedicated to Price "my return to the novel."

Vidal recalled Price as "splendid to talk to, an old-fashioned Platonist in his quetioning style . . . ." Vidal and Price "were as one in our detestation of Christianity and the moral mien that accompanies it like an acid rain."

Prices's novels, said Vidal, display his "idealization of the American past. "He had a view of Arcadia--well, Thebes-that he had impressed upon the Western Reserve." Price "lived in a glowing nativist past." But writing on the modern world in his Globe columns, Price "was shrewd and tough as nails."

Richard Wallace Nathan Comments on Lucien Price

Jonathan Ned Katz writes: In response to the above original column in The Advocate, I was delighted to receive a letter from a reader, Richard Wallace Nathan. In 1957, when Nathan was 19, and in his first year at Harvard, he had worked as a waiter in a summer resort in Nahant, Massachusetts, the Edgehill Inn, where he met and became friends with Price. Nathan had grown up in a middle-class Jewish family and had become aware of some feelings for other men.

Nathan recalled:

- It was a pleasure to wait on him because there was always a smile, a chuckle, there was always maybe a humorous remark. He was a very full and good natured guy. We laughed a lot. He found the world amusing, he found people amusing. He had a fascination with all kinds of people.

- In 1957, he often would say "Why don't you come up in the evening. We'll have a chat -- stop by the room in the evening" And after I had finished what I was doing, at 8 or 9 o'clock at night, I would knock on his door, he would invite me in, he would pour me a glass of port. Well, nobody had ever poured a glass of port for me. And, of course, it was in an elegant little crystal glass. I wasn't drunk, he wasn't trying to get me drunk, but I'm sure it loosened me up, maybe it loosened him him up. No doubt, in retrospect, he saw me as delectable. And I was too naive to know what was going on. And yet, there was always a sense of propriety. Lucien was unique in my cosmos.

Nathan remembered that silver candlesticks decorated Price's apartment, and a plaster mask of Beethovan, and that Price had met the composer Jean Sibelius.

Fifty years Nathan's senior, Price was "the first adult who took me seriously and treated me as an equal," said Nathan. "Price stimulated my interest in literature, encouraged me to think for myself, and made me aware of intellectual powers I did not know I possessed."

In a recorded interview, Nathan answered questions posed by Katz.[3] Asked what Price meant in his life, Nathan replied that as a young man, "I didn't know gay people, which was why he was so important."

Nathan recalled Price:

- He was a vigorous guy. His idea of a beautiful afternoon in his 80th year was to go to Crane's Beach on the North Shore of Massachusetts and take off his clothes and walk naked in the dunes with his hands clasped behind him thinking noble thoughts.

Nathan described how his relationship with Price effected his perception of himself and his sexuality:

- It made my life, and what I might have thought of as base impulses, beautiful. I wasn't a sordid creature. I wasn't someone creeping around in a men's room. That's what was so important.

Nathan said that Price provided him an alternative to the resolutely negative mass media vision of homosexuality:

- Oh, shit, yeah! Lucien was the first man who enabled me intellectually, sexually, personally, to feel whole, to feel good. He respected me as I was. The word 'homosexual' for the longest time, suggested pervert, suggested a men's room affair, or a guy in a movie theater in a raincoat. Lucien was not that. Lucien had relationships,m sexual, personal, with men. he had a kind of special relationship with me. And in additional to all that Lucien had this intellectual curiosity, he had a full life. He was an exciting man who had made it work. In his own way,. Maybe that's why he was so important.

- As I perceived it, Lucien carved out his own life against substantial cultural tradition--sex, politics, religion--very different than his own. He thought of himself as a heretic in all those three departments, and he and people like him paid a price, but that was the only way to live. Lucien was unlike any man I'd ever known.

Richard Wallace Nathan later went on to become one of New York City's Deputy Health Commissioners, and afterward worked in the hospital brokerage business in California. He died of AIDS in 1996. He is said to have once been lover of former New York City Mayor, Ed Koch.[4]

From the Harvard Magazine:

Richard Wallace Nathan, [Harvard] '60 died July 9, 1996 in Los Angeles. He was a former official with the Office Of Management and Budget in Washington, D.C., and a former assistant commissioner in the New York City Department of Public Health. After moving to Los Angeles in 1979, he worked for several environmental groups and served on the board of directors of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. He leaves his mother, Ruth, and a sister, Jane Rothschild.[5]

See also: Junius Lucien Price (January 6, 1883 – March 30, 1964)

Notes

- ↑ Katz, "Glimpses of Gay Arcacdia: Rediscovering the Works of Lucien Price, Unknown Homosexual Emancipation Pioneer", Advocate, November 7, 1988, page 52-53.

- ↑ Vince, Thomas L. "Lucien Price Book Collection at WRA Library".

- ↑ The recorded interview is in The Jonathan Ned Katz Collection, New York Public Library, Rare Books and Manuscripts Collection.

- ↑ Michael Rogers, "New York City Mayor Ed Koch." August 30, 2004 in BlogActive. Accessed June 8, 2012, from Blog Active. Also see: TowlerRoad.com

- ↑ Accessed June 8, 2011 from: [www.harvard60.org/nathan.html Harvard Magazine, Nov./Dec. 1996.]

Bibliography

Columbia University Libraries. Archives. Lucien Price manuscripts, 1951-1958.

Desmond, Jane. Dancing Desires: Choreographing Sexualities On and Off Stage. University of Wisconsin Press, November 7, 2001.

- Price had been attracted to one member of Shawn's troupe, John Schubert, an interest that was apparently mutual (John Schubert to Lucien Price, ...

Dunn, Michael. [Report to Jonathan Ned Katz, in Katz Collection, New York Public Library Rare Books and Manuscripts.]

Foulkes, Julia L. Modern Bodies: Dance and American Modernism from Martha Graham to Alvin Ailey. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press: August 21, 2002. ISBN-10: 0807853674. ISBN-13: 9780807853672

- Lucien Price to Ted Shawn, 14 December 1935, Folder 52, ibid. 25. Lucien Price to Ted Shawn, 8 February 1934, Folder 39, ibid.

Harvard Crimson. Obituary of Lucien Price, unsigned. "Lucien Price '07". April 06, 1964]

HathiTrust Digital Library. Holdings

Katz, Jonathan Ned. "Glimpses of Gay Arcacdia: Rediscovering the Works of Lucien Price, Unknown Homosexual Emancipation Pioneer", Advocate, November 7, 1988, page 52-53.

McClure, W. Raymond. Prometheus; A Memoir of Lucien Price, January 6, 1883 - March 30, 1964.

Nathan, Richard. Interviewed by Jonathan Ned Katz about meeting Lucien Price. Recording. Katz Collection, New York Public Library Rare Books and Manuscripts.]

Price, Lucien.

- All Souls: Volume I. Hellas Regained. Boston, Mass. Boston, Mass. University Press, Inc., 1957. Copyright 1957 by Lucien Price.

- All Souls: Volume II. The Great Companions. Boston, Mass. University Press, Inc., 1962. Copyright 1962 by Lucien Price.

- All Souls: Volume III. The Furies. Boston, Mass.: Nimrod Press, Inc. 1988. Copyright by

- All Souls: Volume IV The Sacred Legion. Fireweed, Book I. Cambridge, Mass.: University Press, Inc., 1955. Copyright 1955 by Lucien Price. [Volume IV of the All Souls novels.]

- All Souls: Volume IV The Sacred Legion. Davencliffe, Book II. Cambridge, Mass.: University Press, Inc., 1955. Copyright 1955 by Lucien Price. [Volume V of the All Souls novels.]

- All Souls: Volume IV The Sacred Legion. Lion of Charonaea, Book III. Cambridge, Mass.: University Press, Inc., 1954. Copyright 1954 by Lucien Price. [Volume VI of the All Souls novels.]

- All Souls: Volume IV The Sacred Legion. Thunder Head, Book IV. Cambridge, Mass.: University Press, Inc., 1951. Copyright 1951 by Lucien Price. [Volume VII of the All Souls novels.]

- All Souls: Volume VIII. October Rhapsody. Boston, Mass.: University Press, Inc., 1958. Copyright 1958 by the Estate of Lucien Price. [Volume VIII of the All Souls novels.]

- Amphion's Lyre : Discourse to the Harvard Glee Club, on the Evening of May 31st, 1945. (1945).

- Another Athens Shall Arise.

- Dialogues of Alfred North Whitehead, as Recorded by Lucien Price.

- Hardscrabble Hellas: An Ohio Academe. Western Reserve Academy; 1st edition (1929). ASIN: B004048MS4

- Immortal Youth, a Memoir of Fred Demmler. Boston, 1919, McGrath-Sherrill Press. [Hardcover. Tan cloth. Has a tipped-in color portrait of the subject. Fred, went to Harvard with Lucien Price, he was known as a promising artist , but died in W.W.I.]

- Litany for All Souls. Beacon Press; 1ST edition (January 1, 1945). ASIN: B003L249U6

- We Northmen.

- William James, Philospher and Man: Quotations and References in 652 Books. Edited by Charles H. Compton. Foreword by Lucien Price.

- Winged Sandals.

Shand-Tucci, Douglass. The Crimson Letter: Harvard, Homosexuality, and the Shaping of American Culture.

Shand-Tucci, Douglass. Ralph Adams Cram: An Architect's Four Quests: Medieval, Modernist, American, Ecumentical.

Titcomb, Caldwell. “Foreword” to Dialogues of Alfred North Whitehead by Alfred North Whitehead and Lucien Price.

Vince, Thomas L. "Lucien Price Book Collection at WRA Library".

Western Reserve Academy: John D. Ong Library. [Lucien Price Book Collection (see Vince above).]