Lester Strong and David Waggoner: "XY on XY," 2008, page 2

ANAGRAMS

by

Lester Strong

THERE ARE TIMES when a sharp emotion pierces through us, unexpected, uninvited. A stab of longing, regret, joy, or guilt, and suddenly we’re transported to a different point in our lives, one until that moment veiled by the accepted and unremarkable round of our daily activities.

Midautumn, midafternoon, midway through that most prosaic of activities: pedaling a stationary bicycle. One second I’m sweating and trying to concentrate on the page of print before me I’m reading in an ever less successful attempt to ward off a dreary boredom. The next I’m hearing in memory the voice of a woman speaking over the phone—and once again reading anagrams from a scrawled note on a loose sheet of paper.

First the voice: “Is this L—? Yes? Well, this is John T—’s mother. We haven’t spoken together in many years but”—a sob—“I wanted to let you know that last Wednesday John jumped off a bridge and”—another sob—“killed himself.”

Stop the reading, stop the boredom. Instantly I’m transported back I time—not just to the phone call from John’s mother six months before, but further back, much further, over thirty years to the early 1960s and the night John and I met. The night we fell in love.

This is upset, confusion and upset. A numbness I haven’t recognized until this moment lifts abruptly and feelings beyond the shock I was aware of after that phone conversation in March reveal themselves with a startling clarity. Although, curiously, the pedaling and sweating continue unabated.

John and I met in the early fall of our senior year in high school. I use “met” with a peculiar emphasis because we’d known each other for two years before that, sharing classrooms and teachers of music and German. But until that revelatory meeting our senior year at the home of a mutual friend, there had been nothing more. My own awareness of John had been at best casual. He later admitted to more than a casual interest in the books he’d noticed I always seemed to carry with me. D. H. Lawrence’s The Rainbow and Women in Love, Lawrence Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet, Rimbaud’s A Season in Hell, Dostoyevsky’s novels—there were more, and he could name most of them. But until our meeting at the home of our friend, we’d never spoken personally. I doubt we’d ever spoken impersonally. I can’t remember.

The night we met, though, we spoke. We spoke and spoke. I don’t know what our mutual friend or his family thought, but we didn’t stop. When it was too late to stay at our friend’s any longer, we left, drove our parents’ cars a block away and parked, then huddled in my parents’ car talking until early morning. Finally we had to go our separate ways. John was assertive enough to ask for my phone number before driving off, so that a few hours later, around eight o’clock, he called. I gave him directions to my house, and we talked the rest of that day also.

Revelation, truly. Our high school was in turmoil that year—we the baby-boom generation had arrived in force and there were too many students, too few classrooms, not enough teachers. There were also many very simple multiple-choice tests, and that was fortunate because I don’t remember studying much from then on. I just remember being in love, stunningly, overwhelmingly, never-a-moment-to-lose being in love.

First love. I was gay—in those days I would have said homosexual—and keenly aware of it. And knowing I was gay, I longed for a—longed for— Well, from the night we met I longed for John. Slim, fair-skinned, of medium height, with longish dark hair spilling over green eyes, he represented for me a kind of physical perfection. His clothes weren’t of the skin-tight variety, but his jeans fit perfectly over a rounded rump whose smooth nakedness, I learned in the course of time, had the textured whiteness of mother-of-pearl. He also had a nervous energy about him that all but exploded in his every move. Very attractive, that energy. Very. And in its explosiveness perhaps a harbinger of things to come.

First love. Our falling in love was a mutual event, and when I pushed, John acquiesced after a fashion in our having sex together. Anyway in our trying to have sex. Twice. I still remember the intense excitement I felt on first taking his cock into my mouth—and I remember how he gasped in surprise. Even our first kiss is etched in my memory. Two men with lips touching, tongues attached, is still a potent erotic image for me, one whose sudden welling up in the midst of workaday life signals the rebirth of sexual need after a previous satedness.

But if our falling in love was mutual, the sex between us was not. John’s surprise at the acts I wanted to engage in turned to frowns, then rejection. In short order he pulled away from that part of our being together, and I have no doubt his discomfort over our sex helped precipitate his own direct move into heterosexual experiences a short time afterward.

Abruptly, with a great deal of pain, I learned a defining truth: John was not gay. Clearly.

Still, from the first evening we met, and lasting far beyond the short length of our unsuccessful physical affair, there was between us a tie more important than sex: a longed-for intermingling, an attempted merging of our two persons into one. The “need” we dubbed it, and it cut deeply into both of us. It was an acknowledged bond neither of us was willing to relinquish for years, despite other friendships, other loves, even John’s subsequent marriage and two children. It started with Rimbaud’s A Season in Hell, then moved on to Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and The Dharma Bums, which we read obsessively together. In those days the Beats were still cultural royalty, and we imagined ourselves the new Kerouac-Cassady. One person, not two. Of course we were the ones joining our names in a way probably never contemplated by Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady. But we dreamed of writing a new literature together that would be post-Beat, that would say something new, do something big.

We dreamed, anyway. And above all, I suspect, we hoped our dreams would lift us out of our limping selfhoods into a rarified realm of feeling-good, feeling-whole—and definitely feeling removed from our parents’ workaday world and the seemingly quite ordinary and mundane life of the small western city we found ourselves confronting each day. We never stopped to ask precisely just what we wanted. But it apparently had to do with movement: We drove around that town obsessively during the free afternoons our half-day schedule at a crowded high school blessedly provided us with, as obsessively as we read the Beats or Rimbaud. Only it went nowhere. The same for the writing: impossible feelings, impossible good, impossible wholeness. I can see that now. Looking back, the fantasies were pompous, ludicrous, typically adolescent. Certainly no literature came of them. But their hold had the clench of steel, so that moving beyond them was for me very difficult indeed. And for John? According to his mother: “He talked about you all the time. He said he wanted to get back to writing.” The clench of steel. Yes.

Also from his mother: “John was diagnosed as schizophrenic. He lived in a half-way house, and was on medication which”—a sob—“didn’t stop the voices he heard all the time telling him what to do, what to feel.”

Schizophrenia. Perhaps I heard its echoes early on in our involvement. Because if John’s and my need to merge was obsessive, the rifts between us were just as powerful. The first rift, of course, arose from our differences over sex, bridged through the “need” that bound us together with a greater strength. The second rift seemed less important at first, but proved ultimately more divisive. That was drugs. Pot, hash, acid, speed—the names today whiz through my memory almost as dizzily as the substances themselves rushed into John’s life. That was in our college days, the “need” having driven us to enter the same school. By the mid-sixties everyone was trying pot, but John tried everything. And at least for a number of years didn’t quit. I’ll never know all the drugs he took; I’ll never know how often or how long he took them. I didn’t want to know at the time because it frightened me. Here if anywhere lay the seeds of the end of our merging. Through drugs John moved into a world I was too fearful to enter myself, and little by little our lives drifted apart.

Did the drugs contribute to John’s schizophrenia? I can’t speak as a medical expert. But I remember the letters I received from him over the years, which from the early seventies on became ever more perplexing, then frightening, in their incomprehensibility. This was after I had moved east, and he had moved further west and north, to Tacoma where his parents now lived. There was one last meeting between us in person, in the mid-seventies, and he was as incomprehensible in person as he had become in writing. But it is the letters that remain the most vivid in memory, or at least my reaction to them. Crazy, rambling letters. After the first few I stopped reading them; then I stopped saving them; finally in a frenzy of upset, I tore them all up and felt only relief. Over the years I’ve felt some regret at that ripping, but not much. Keeping them was too painful.

The letters were the third and almost final rift between us. But there was one more: his calls over the phone. Those started in the late seventies or early eighties, only once or twice a year, invariably from Tacoma. At first he called collect, but that stopped when I stopped accepting the charges. Then he found access to other people's phones—most likely his parents’—and the calls resumed.

His phone conversations were marginally less incomprehensible than his letters, but also invariably nostalgic: descriptions of threats he claimed he was receiving from people whose names I didn’t recognize or of chaotic trips he’d taken up and down the West Coast, then talk about how he wanted to come east, how we’d have a cup of coffee together, how it would feel like old times. Of course it wouldn’t have been old times. It would have been something I no longer wanted, no longer could tolerate. I came to dread those calls, but if I could turn down requests to reverse charges, once we started talking I couldn’t stop the conversations themselves. I spoke minimally, but I listened, transfixed.

The truth was that over the years I’d made a life apart from John happier than anything I’d ever known with him. It might sometimes involve tedium—riding an exercise bicycle—but it also involved new ties, new love, new ways of relating more satisfying than John’s and my ill-starred attempt to merge our disparate personalities.

A deeper truth: This satisfying life had no place for John. I could sense his loneliness and pain, but could do nothing to assuage them. Could do nothing even to attempt assuaging them.

A still deeper truth, one not apparent to me until that instant on the bicycle when I recalled his mother’s phone call: I carried some part of John’s and my old dependency into my new life. For years I could tear up letters unread and say no to accepting reverse phone charges, but I listened transfixed to his calls. I could not hang up on that voice. Somewhere within myself I was still listening to old needs, old satisfactions. To old love.

A last remembered comment from John’s mother over the phone: “I called because we knew he kept in touch with you and saw from our telephone bill that he phoned you just a couple of weeks ago. Did he”—a sob—“say anything, give any hint, that he was thinking of—planning to—?”

Which brings me to the anagrams and scrawled note.

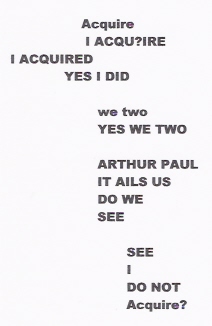

John’s mother couldn’t finish her question, but I could truthfully answer no—no hint he was planning to do anything. Not a word. Nothing. Then two days after her call, I received in the mail an envelope—no return address, its postage affixed to the wrong side, the cancellation date smeared and unreadable, the word Tacoma just legible. On the sheet inside were the following words scrawled in block letters:

AIDS. SIDA. Anagrams. One last message from John, clearly. This one neither torn up nor thrown away, but still in my possession.

There are many routes to AIDS: drugs, needles, transfusions, the varieties of sex. I had managed to miss them all, through new ties, new love, new ways of relating more satisfying than John’s and my attempts to merge—and no doubt through a good deal of luck. But had John traveled one of them?

A sharp emotion pierces through us, unexpected, uninvited, and suddenly we’re transported back to a different point in our lives. It’s no longer the same precise moment, we’re no longer precisely our old selves. But we are pierced: as if the intervening years have failed to intervene.

I’ve looked up the passage I was reading that fall day on the stationary bicycle when the thought of John flashed into memory: “Who knows, my God,” Kerouac cries, “but that the universe is not one vast sea of compassion actually, the veritable holy honey, beneath all this show of personality and cruelty. . . . Live your lives out? Naw, love your lives out.”

Kerouac. Vintage Kerouac. And a vintage message. Almost anachronistic. After all, this is the age of AIDS, of safer sex, of exercise bicycles that must be pedaled no matter what the upset. It’s not the age of dharma bums.

And yet.

John wasn’t gay. Clearly.

In my mind I hear the echo of his voice over the phone, clearly.

I don’t want to hang up. I don’t want to forget.

Perhaps in the age of AIDS Kerouac’s message isn’t so anachronistic after all.

“Love your lives out.”

Clearly.

Dialogue: Blood Brothers

David Waggoner: In “Anagrams,” what’s the difference between love and sex?

Lester Strong: An interesting question. The story is largely—though not totally—autobiographical, and like the story’s narrator, in real life I certainly lusted after John. His ending the sex between us was a big shock, especially because the love feelings didn’t stop for either of us. But I think in the end it taught me that love and even eroticism don’t respect the boundaries of sexual orientation. John and I were involved in some strange way for years and years, even after the point at which I wasn’t thinking about him on a day-by-day basis. The feeling of connection and of needing to feel connected never stopped, and that connection never stopped being sexual at some level. I don’t know where to put that.

DW: Early on in the story, you describe the narrator and John falling in love and John acquiescing in trying to have sex. John later kills himself. Is there any link between the two? Does the narrator feel in some way that he was potentially the cause of John’s death?

LS: I don’t think so. No.

DW: The story’s not quite that dark?

LS: I don’t think there’s any link between the sex and John’s suicide. Too much time had passed.

DW: I see a parallel between “Anagrams” and “New Story” in that in my story there’s a gulf between the narrator and Tim because of the difference in their HIV sero-status while in your story there’s a gulf between the narrator and John because of John’s schizophrenia. Could you comment on that?

LS: It’s John’s schizophrenia that drives the biggest wedge between the narrator and John. Over the years it becomes clear to the narrator that there’s something wrong with John mentally. But it isn’t until John’s mother says over the phone that he was diagnosed as schizophrenic that it all falls into place. I’ve since learned that schizophrenia usually manifests itself in late adolescence or early adulthood, and that’s the period when the narrator and John first become involved with each other. But at the time the narrator doesn’t know what’s going on. He just sees somebody who’s acting very strangely. He’s often hurt by the behavior, but doesn’t understand what’s causing it. In my own life, I put it off onto John’s use of drugs. I said to myself, “He’s been done in by drugs,” when instead the drugs were probably a way he tried to self-medicate himself for emotional problems he couldn’t deal with in any other way.

DW: Some people when they read the story in A&U said they didn’t understand the meaning behind the anagrams AIDS and SIDA. That is, they wondered if John really did have AIDS. Or do the anagrams symbolize some kind of “emotional AIDS”?

LS: I’m not sure myself. There was desperation behind John’s suicide, and he didn’t live his life in a safe way. But I don’t know if his desperation was related to AIDS. Still, he didn’t refer to AIDS for no reason at all. Schizophrenics often communicate through symbols. John killed himself in the early 1990s, before the antiretrovirals came out. Maybe AIDS for him symbolized being somewhere so frightening and dangerous he didn’t want to live there any longer.

DW: What I really appreciate in the story is the pain the narrator expresses. Could you comment about that pain?

LS: It’s the pain of the loss of love sustained over many decades. It was love lost not because there was no love but because there was no effective way to express it on either side. The description of the narrator’s reactions is meant to be painful, right up to the end of the story. And yet the pain is not the primary emotion. It’s the love that was the most real despite all the pain.

Another way of saying this is that despite the pain the narrator never wants to give up the love. The love somehow is more important than the pain, greater than the pain, and in a way the pain reinforces the love.

DW: Does the mother character symbolize a society that doesn’t understand the relationship and emotional closeness a straight man can have with a gay man?

LS: Yes. She stands for an uncomprehending society that takes for granted a friendship between two guys but understands nothing of its complexity or the needs it meets. But I’d add that as a mother her priorities were of course different than those of the narrator. For her, it was the loss of her son that was important.

DW: I’ve said I see parallels between “New Story” and “Anagrams.” Do you see parallels too?

LS: They’re both about frustrated love, love that isn’t consummated at the point when it should have been consummated and as a result causes unhappiness for many, many years. Both stories are about male-male feelings, how deep the feelings can go, and how legitimate they are. They describe deep feelings of closeness that bring to mind the phrase “blood brothers”—

DW: With HIV around, I don’t think “blood brothers” is such a good image.

LS: You’re right. Anyway, I think it goes considerably beyond the notion of blood brothers. Could we come up with a new phrase? “Semen brothers”? “Cum brothers”? In terms of gay desire, it involves the wish to become one with another male, and for me that brings to mind the joy of mixing your semen with that of the guy you love, strictly in a safe way, of course. In our society that is definitely not recognized as a legitimate need.

DW: Both “New Story” and “Anagrams” have narrators that are emotionally dissatisfied. But I think “Anagrams” is more satisfying at some level for the reader because the narrator is able to understand his dilemma, whereas the narrator in “New Story” is not.

LS: I disagree. I think the stories are speaking at different emotional levels. “Anagrams” has a worked-out, coherent intellectual framework from start to finish. I think “New Story” is quite rightly somewhat more formless, mainly because AIDS is right at its center—this mysterious illness that turned the whole world topsy-turvy for gay men in a few short years. I don’t think “New Story” is any less satisfying than “Anagrams.” It just opens out into a sense of wonder. And that’s a very legitimate aim in literary works, to engender a sense of wonder.

Copyright © 2008 Lester Strong and David Waggoner. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any other information retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the authors.