Lester Strong and David Waggoner: "XY on XY," 2008, page 5

Dialogue: Faces Not Needed

Lester Strong: David, none of the drawings we’ve included in this book shows men with faces. Some are even headless. They’re just torsos, or torsos with dicks. To me that suggests something about the part played in gay male sexuality by anonymous sex. What do you think about anonymous sex and the role it plays in gay male life?

David Waggoner: I think anonymous sex and gay sex are oftentimes in our society interchangeable terms. There are heterosexuals who are promiscuous. But the very first gay sexual experience I had was with a guy I only spent about five minutes with. How many heterosexual boys can say that about their first sexual experience with a girl?

LS: Even with adult heterosexuals who are promiscuous, there’s a kind of social ritual. A man may be screwing five women a week or a woman five men a week, but they’re going out for meals or drinks with each other first. There’s a little socializing. I’ve never heard of a place in a park or on a pier where men and women go just for anonymous quickies.

DW: I can think of one example—areas where straight men go to pick up prostitutes.

LS: You’re right.

DW: But I know of almost no female heterosexuals—or lesbians—who have sex with strangers unless they’re prostitutes or rape victims. And the latter isn’t sex.

LS: What do you think that says about gay male psychology? Why for so many gay men doesn’t the face—by which I mean the social identity—of their sex partners matter that much?

DW: I think anonymous sex fetishizes the sexual experience. Or it fetishizes certain bodies parts—the cock or the asshole. If you don’t have a face to go with the cock or the asshole, it can feel safer. It can also be damaging or limiting, to some extent, although I think a lot of gay men get over that.

LS: Get over what? The need for anonymous sex? Or the damage and limitations?

DW: Both.

LS: How can the need for anonymous sex be damaging?

DW: It was damaging for me personally because I didn’t think that a normal relationship could be possible in the homosexual realm. I didn’t think I could have a worthwhile relationship, one that had a deeper meaning than just the genital experience.

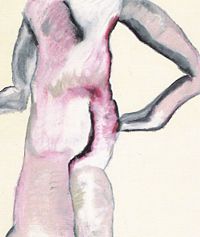

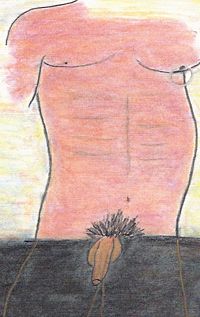

I think the drawings by me we’ve included in the book [Blue Pose, Brown Pose, Red Pose] are about that. I think I was doing them at a very disjointed period of my life, sexually speaking, and they represent my attempts to come to terms with the anonymous aspect of gay sex I was experimenting with. They’re gay sexual encounters done as drawings.

LS: How are they encounters? Each drawing depicts only one individual.

DW: Perhaps I shouldn’t say encounters so much as visual momentos of sexual encounters I’d had. They were done in a drawing class while I was in college. There was a male model, and around twenty students in the class. I remember the drawing instructor saying: “Why don’t you put heads in your drawings? You never put heads in your drawings.” Everyone else had heads in their drawings.

LS: What did you reply?

DW: I don’t remember. I was probably too embarrassed about him pointing this out to say much of anything. I think I was also embarrassed because I was using the drawings to deal with my sexuality.

I was creating amputations, basically. There were no heads. Sometimes there weren’t even feet. The genital area, torso, chest, and ass seemed more important to me than a whole body. I was using the model in a different way than everyone else was.

LS: To me, all three drawings look somewhat expressionistic.

Copyright © 2008 Lester Strong and David Waggoner. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any other information retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the authors.

DW: I think a lot of the students were aiming for a more realistic approach. My drawings involve distortion.

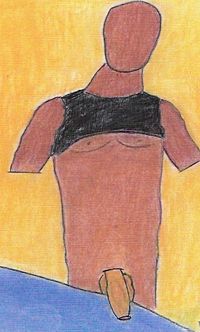

Your own three drawings [Gold Leaf, Black T, Silver Arrow] involve amputations too. One of them has no head, two have heads but no facial features, and none has full limbs. Why?

LS: My work came out of a drawing workshop I was in—not a drawing class, but a drawing workshop for gay men. We met once a week for three hours, each time with a different male model who undressed during that time in a series of poses. I must have done dozens, even hundreds, of drawings in that workshop. They were all line drawings in pencil or charcoal, and some were quite nice. But these three came out of the failures I produced, drawings that for some reason or other just didn’t work. I didn’t throw the failures away, but would study each of them occasionally, thinking, “How can I make this enjoyable to look at?” Eventually it came to me that they could be reworked in color in an expressionist manner, making a virtue of their defects.

DW: You didn’t think faces or hands and feet would make them enjoyable?

LS: There were some men with beautiful faces who modeled for that workshop, but I’d say that ninety-eight percent of the time what interested me were the torsos. I don’t think this came out of dealing with my sexual encounters, anonymous or otherwise. I’ve had next to no anonymous sex in my life, and I’d been in a full-blown relationship for nearly thirty years during the period when I was in the workshop. But I do think my almost exclusive interest in torsos came out of my dealing with sexual issues.

DW: Dealing with feelings of discomfort?

LS: Yes. And I think the discomfort had to do with the workshop itself.

DW: Why? I understand my discomfort. I was dealing with my sexuality through my art in a college classroom, where no one knew I was gay. That was twenty years ago, when being openly gay was much more of a problem than it is today. I felt it was dangerous for me to explore my sexuality so publicly. But your drawings were done just a few years ago, in a room full of gay men and a comfortable atmosphere accepting of gay sex.

LS: I think at some level I felt threatened by the sexual atmosphere. It wasn’t being around gay men. It was the steamy, sexual, nature of the whole enterprise. Here we were, fifteen or twenty gay male artists in a room drawing beautiful men as they stripped off their clothes little by little. There was nothing formal or academic about this. It was meant to be erotic. The workshop was for gay men who wanted to produce erotic drawings, and although nothing overtly sexual happened, it was a highly charged sexual atmosphere. Nor was I the only workshop artist who felt this way. One guy told me he found the atmosphere so charged he could allow himself to attend only once in a while. Other men told me they had been so shaken on a sexual level during some of the sessions that they hadn’t drawn anything they considered good.

DW: You said you find my drawings expressionistic. Speaking formally about yours, I find them more classicizing and simplifying. Silver Arrow seems almost like a piece of Greek statuary, with broken-off arms and no head.

LS: I can see what you mean. I wasn’t aiming at anything realistic in the drawings. Perhaps I simplified them because I was dealing with my own sexuality rather than the beauty of the models themselves.

DW: Which of our drawings do you think are dealing more with sexual anxiety and which more with formal artistic issues having to do with composition or color? Or are all of them dealing with both kinds of problems?

LS: I think they’re all dealing with both. There are definitely formal elements in what I was doing because I was trying to produce something interesting to the eye out of originals that failed to do much of anything, visually speaking. At the same time, I was expressing my own sexual anxiety over being confronted with such beautiful, desirable men each week. I see pretty much the same concern with both formal elements and sexuality going on in your drawings too.

DW: Even though your drawings and mine were done twenty years apart.

LS: I guess formal considerations in art or anxieties over sexual subject matter know no boundaries, even temporal boundaries. Besides, gay sexuality and desire may be more open these days than in the past, but they’re still culturally problematic.

DW: I think it’s the issue of disclosure, too. How much of yourself do you disclose through art, and how much do you keep from being expressed?

LS: Yes. Disclosure certainly is a problem. In some ways, it’s been the center of all our discussions in this book, hasn’t it?

About the Authors

Lester Strong is Special Projects Editor for A&U magazine. Educated at St. Johns College in Santa Fe, NM, and The New School for Social Research in New York City, he holds a graduate degree in philosophy. His writings on the visual, written, and performing arts have appeared in publications from coast to coast, and his art is in a number of public and private collections.

David Waggoner is founder, publisher, and editor-in-chief of A&U, since 1991 America's premier HIV/AIDS magazine. Educated at Brown University, he holds a degree with concentrations in studio art, art history, and creative writing. He has workshopped his stories with Toni Morrison, John Hawkes, Angela Carter, and Robert Coover. His visual art is in many private collections around the country.

Copyright © 2008 Lester Strong and David Waggoner. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any other information retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the authors.