Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi: October 2, 1869 –January 30, 1948

From OutHistory

Jump to navigationJump to searchReviews of Joseph Lelyveld's biography, Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India (2011), react to the revelation of an intense, intimate, romantic relationship between Gandhi and architect and bodybuilder, Hermann Kallenbach.[1]

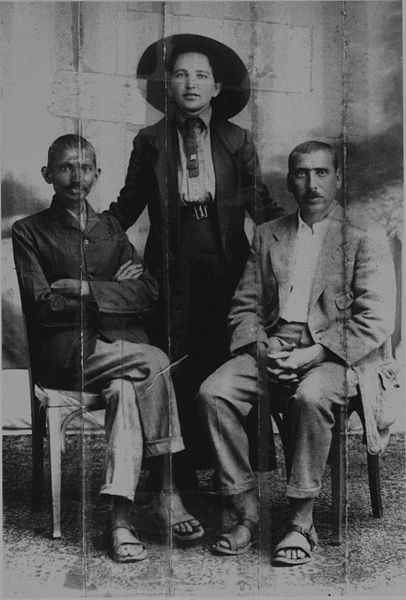

Right: Gandhi, Sonia Schlesin (Gandi's assistant), Hermann Kallenbach, 1913

Wall Street Journal, March 26, 2011

In a negative review in the Wall Street Journal on March 26, 20011, Andrew Robert says,

- Gandhi's pejorative reference to nakedness is ironic considering that, as Mr. Lelyveld details, when he was in his 70s and close to leading India to independence, he encouraged his 17-year-old great-niece, Manu, to be naked during her "nightly cuddles" with him. After sacking several long-standing and loyal members of his 100-strong personal entourage who might disapprove of this part of his spiritual quest, Gandhi began sleeping naked with Manu and other young women. He told a woman on one occasion: "Despite my best efforts, the organ remained aroused. It was an altogether strange and shameful experience."

- Yet he could also be vicious to Manu, whom he on one occasion forced to walk through a thick jungle where sexual assaults had occurred in order for her to retrieve a pumice stone that he liked to use on his feet. When she returned in tears, Gandhi "cackled" with laughter at her and said: "If some ruffian had carried you off and you had met your death courageously, my heart would have danced with joy."

- Yet as Mr. Lelyveld makes abundantly clear, Gandhi's organ probably only rarely became aroused with his naked young ladies, because the love of his life was a German-Jewish architect and bodybuilder, Hermann Kallenbach, for whom Gandhi left his wife in 1908. "Your portrait (the only one) stands on my mantelpiece in my bedroom," he wrote to Kallenbach. "The mantelpiece is opposite to the bed." For some reason, cotton wool and Vaseline were "a constant reminder" of Kallenbach, which Mr. Lelyveld believes might relate to the enemas Gandhi gave himself, although there could be other, less generous, explanations.

- Gandhi wrote to Kallenbach about "how completely you have taken possession of my body. This is slavery with a vengeance." Gandhi nicknamed himself "Upper House" and Kallenbach "Lower House," and he made Lower House promise not to "look lustfully upon any woman." The two then pledged "more love, and yet more love . . . such love as they hope the world has not yet seen."

- They were parted when Gandhi returned to India in 1914, since the German national could not get permission to travel to India during wartime—though Gandhi never gave up the dream of having him back, writing him in 1933 that "you are always before my mind's eye." Later, on his ashram, where even married "inmates" had to swear celibacy, Gandhi said: "I cannot imagine a thing as ugly as the intercourse of men and women." You could even be thrown off the ashram for "excessive tickling." (Salt was also forbidden, because it "arouses the senses.")[2]

New York Times, March 29, 2011

In his positive review in the daily New York Times on March 29, 2011, Hari Kunzru says:

- While Gandhi’s political rivalries and his shortcomings as a husband and father have been publicly debated, Mr. Lelyveld’s frank discussion of Gandhi’s erotically charged friendship with the German-Jewish architect and bodybuilder Hermann Kallenbach is likely to ruffle feathers, especially in a country where homosexual activity was a criminal offense until 2009.

- Gandhi left his wife to live at Kallenbach’s house in Johannesburg for a period, and Kallenbach donated to Gandhi the 1,100 acres that became their communal Tolstoy Farm in 1910. As Mr. Lelyveld notes, “in an age when the concept of Platonic love gains little credence,” the romantic tone of their letters (including pet names) is likely to be read as indication of a straightforward homosexual intimacy.

- Yet it is also clear in Mr. Lelyveld’s account that Gandhi’s celibacy was a profound and deeply felt position. His vow of brahmacharya, or self-imposed celibacy, taken in 1906, was to become the foundation of his moral authority in the eyes of the Indian masses. Nearing 70, he had a wet dream. The “degrading, dirty, torturing experience” was shattering, he wrote. It “made me feel as if I was hurled by God from an imaginary paradise where I had no right to be in my uncleanliness.”[3]

New York Times, March 31, 2011

A report from Kochi, India, says that reviews in the U.S. of Joseph Lelyveld's new biography of Gandhi is causing controversey among conservatives in India:

- The problem, say those who have fanned the flames of popular outrage this week, is that the book suggests that the father of modern India was bisexual.

- The book’s author, Joseph Lelyveld, does write extensively about the close relationship Mohandas K. Gandhi had with a German architect, but he denies that the book, “Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India,” makes any such argument.

- . . .The crux of the controversy seems to be the intersection of two subjects on which Indians have strong views: sexuality and Gandhi.

- On the first point India is quite conservative, but the recent rapid growth of its economy has helped loosen attitudes, especially among the large youth population. In 2009 the Delhi High Court struck down a British-era law against sodomy, a ruling seen as a watershed for gay rights. Nevertheless most gay Indians would not feel comfortable coming out.

- . . .The controversy appears to have started because of reviews in publications in the United States and Britain, including one in The Wall Street Journal, asserting that the book provides evidence that Gandhi was “a sexual weirdo, a political incompetent and a fanatical faddist.”

- That review, by Andrew Roberts, a British historian, argued that Gandhi was in love with Hermann Kallenbach, the German-Jewish architect with whom Gandhi lived in Johannesburg, and it cited letters from Gandhi to Mr. Kallenbach, which are quoted in “Great Soul.”

- Gandhi expresses great fondness and yearning for Mr. Kallenbach in the letters, telling him that his was the only portrait on Gandhi’s mantelpiece, opposite the bed, and that cotton wool and Vaseline were “a constant reminder” of him.

- . . . In the book Mr. Lelyveld writes, “One respected Gandhi scholar characterized the relationship as ‘clearly homoerotic’ rather than homosexual, intending through that choice of words to describe a strong mutual attraction, nothing more.”

- But Mr. Lelyveld then acknowledges: “The conclusions passed on by word of mouth in South Africa’s small Indian community were sometimes less nuanced. It was no secret then, or later, that Gandhi, leaving his wife behind, had gone to live with a man.”

- Although Mr. Lelyveld does not draw a conclusion about the relationship in the book, he writes, “In an age when the concept of Platonic love gains little credence, selectively chosen details of the relationship and quotations from letters can easily be arranged to suggest a conclusion.”[4]

- . . . “All I can claim is that I dealt with that material more extensively with an eye to the general public than anyone previously,” Mr. Lelyveld said. “But it’s not a central preoccupation. My book is about Gandhi’s struggle for social justice, not his intimate relationships. But he was a complicated man, and the two are linked.”

Notes

- ↑ Joseph JLelyveld. Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 2011.

- ↑ Andrew Robert. "Bookshelf. Among the Hagiographers. Early on Gandhi was dubbed a 'mortal demi-god'—and he has been regarded that way ever since". Wall Street Journal, March 26, 2011, page ?

- ↑ Hari Kunzru, "Books of the Times, Appreciating Gandhi Through His Human Side", New York Times, March 29, 2011), page ?

- ↑ Vikas Bajaj and Julie Bosman. "Book on Gandhi Stirs Passion in India". Datelined: KOCHI, India. March 31, 2011, pages C1, C4.

<comments />