Peter Sewally - Mary Jones, June 11, 1836

The "Man-Monster"

Adapted, with permission, from Jonathan Ned Katz's Love Stories: Sex Between Men Before Homosexuality. Copyright by Jonathan Ned Katz, 2001. All rights reserved.[1]

The Pick-Up

About ten o’clock on the night of Tuesday, June 11, 1836, in New York City, a master mason named Robert Haslem, a white man was walking home after a liaison with a woman he had picked up earlier that evening, as the New York Herald later reported.

On Bleecker Street, Haslem met a black woman, Mary Jones, dressed "elegantly and in perfect style," with white earrings and a gilt comb in her hair.[2] The Herald's rival, the New York Sun, added that Mary Jones also went by the names "Miss Ophelia," "Miss June," and "Eliza Smith."

Haslem or Jones initiated a conversation-the newspapers differed. Haslem then asked Jones, "Where are you going my pretty maid?" and volunteered to go with her.

Before they set off "on this tour of pleasure," said the Herald, she "lovingly threw her arms around him and strained him to her heart." Then, "these delicate preludes having ended, they proceeded onwards, until they arrived at an alley in Greene Street [known then as a site of prostitution], which having entered *****" Here, a series of asterisks in the Herald's report suggest, as clearly as the missing words, a sexual act.

Haslem and Jones "had some further conversation" in an alley, said the more reticent Sun, "where the prisoner again had his arms about complainant."[3] Afterward, on his way home, according to the papers, Haslem discovered that his wallet and ninety-nine dollars were missing. In their place he unaccountably found the wallet of a man he did not know, with a bank order for the then large sum of $200.

Haslem sought out the man who, at first, denied ownership of the wallet, but then admitted he had had his pocket picked the previous evening, under the same circumstances as Haslem. He had been "too wise," however, "to expose himself" by reporting the theft to the police.

Next morning the determined Haslem confessed his story to a Constable Bowyer who, that evening, set out to find Mary Jones. Around midnight, on the Bowery, Bowyer passed a black woman and, according to the Herald, "thinking that this might be the one he sought" (and assuming the right to his gaze), looked at her face and "made up his mind that he was right."

"Where are you going at this time of night?" he asked. "I am going home, will you go too?" she answered. He agreed, and "she conducted him to her house in Greene Street, and invited him in."

He declined, "with great regret," but later walked her to an alley where she asked him, as the Herald put it, "to reenact the scene of the previous evening" with Haslem. She then "proceeded to be very affectionate:' and Bowyer arrested her.

"A tussle ensued:' the Sun reported, during which the prisoner allegedly took two wallets from her bosom and threw them away. One turned out to be Haslem's. On the way to the watch house, Jones allegedly tried to ditch another wallet but was caught. With Jones locked up, the constable took her key, searched her apartment, and found, allegedly, a number of other wallets.

A Discovery

Constable Bowyer then searched Mary Jones and, said the Sun, "for the first time discovered that he [Jones] was a man." Until that time, said the paper, Bowyer had had no doubts about Jones's sex.

The papers suggested that the complainant, Haslem, had not reported, or had not known that Jones was a man.[4] Can we believe this? Might Haslem have recognized a cross-dressing prostitute but not cared about his sex? Or, could Haslem have sought sex with a cross-dressed woman-man? The known documents do not tell us.

"Bowyer also discovered," said the Sun,', that the prisoner, "to sustain his pretension, and impose upon men"-- here seventeen words in clumsy Latin complete the sentence. Translated, the phrase says that the woman impersonator "had been fitted with a piece of cow [leather?] pierced and opened like a woman's womb ["vagina" is the intended word], held up by a girdle."[5] Educated, Latin-reading, upper-class men could apparently contemplate such details without harm; women and lower-class persons of either sex could not.

The Trial

On June 16, five days after Haslem's fateful meeting with Jones, the prisoner, charged with grand larceny, was tried for stealing Haslem's wallet and money. He was not prosecuted for "sodomy," apparently because he had not participated in anal intercourse.

The accused appeared in court, the Sun reported, "neatly dressed in female attire, and his head covered with a female wig," seemingly his outfit when arrested. Did the prisoner choose to be tried in female clothes? Or was this the court's doing? We do not know.

The spectacle of a cross-dressed black man, and of the victimized Haslem, the Herald reported, provided "the greatest merriment in the court, and his Honor the Recorder, the sedate grave Recorder laughed till he cried."

During the trial, the Sun reported, someone in the audience, "seated behind the prisoner's box, snatched the flowing wig from the head of the prisoner." This "excited a tremendous roar of laughter throughout the room."

Do not we sense here a note of hysteria, suggesting submerged anxieties about sexuality, gender, and race, each highly charged emotionally and politically?

Sewally's Testimony

A legal transcript of the prisoner's examination recorded the words he uttered in his own defense; a brief, rare, first-person voice from America's sexual past. Certainly, though, the situation of his interrogation skewed his words.[6]

Asked his age, place of birth, business, and residence, he answered: "I will be thirty three Years of age on the 12th day of December next, was born in this City, and get a living by Cooking, Waiting &c and live No. 108 Greene St."

"What is your right name?" he was asked. "Peter Sewally--I am a man," he answered.

Asked "What induced you to dress yourself in Women's Clothes?" he answered:

I have been in the practice of waiting upon Girls of ill fame and made up their Beds and received the Company at the door and received the money for Rooms &c and they induced me to dress in Women's Clothes, saying I looked so much better in them and I have always attended parties among the people of my own Colour dressed in this way -- and in New Orleans I always dressed in this way -- .

He added: "I have been in the State service" - his military duty was offered, apparently, as plea for the jury's forbearance.

Asked if he had stolen Mr. Haslem's wallet and money, Sewally answered: "No Sir and I never saw the Gentleman nor laid eyes upon him. I threw no Pocket Book from me last night, and had none to throwaway, and the Pocket Books now Shown me I never Saw before --." Not knowing how to write, Sewally signed his statement with the letter X.

The Press Reports

The following day, June 17, the Herald and Sun both carried detailed stories of the case. The Herald was fairly open about the sexual activity associated with the prisoner's cross-dressing and pickpocketing: "Sewally has for a long time past been doing a fair business, both in money making, and practical amalgamation, under the cognomen of Mary Jones." The word "amalgamation" was used often in the nineteenth-century United States to refer to sexual contacts between different races.

During the daytime, added the Sun, Sewally "generally promenades the street, dressed in a dashing suit of male apparel, and at night prowls about the five points and other similar [poor, disreputable] parts of the city, in the disguise of a female, for the purpose of enticing men into the dens of prostitution, where he picks their pockets if practicable, an art in which he is a great adept."

Combining a daytime career as a dashing man and nighttime work as a cross-dressed woman was certainly unusual in the paper's view. But it made no overt link between Sewally's cross-dressing and his erotic intercourse with men. He was presented as an eccentric, not a "sodomite." nor was he identified by any other such label.

"Numerous complaints of robberies so perpetrated by him had been made at the police office at sundry times," said the Sun, "but owing to the scruples of the complainants against exposing themselves in the Court ..., on trial, they have generally abandoned their complaints, and their stolen money, watches, &c." This echoed earlier comments in the "sporting press" that men innocent of sexual activity with men, when blackmailed by sodomites, were too fearful of any public association to prosecute them in open court.

Large sums were alleged to be carried by Haslem and the other victimized man. If those sums were typical, those who were robbed and who made no complaint must indeed have had strong scruples about exposing themselves to public scrutiny.

But what, exactly, were such men embarrassed about? Were they ashamed to be exposed as the patrons of a female prostitute, or a black female prostitute? Or were they ashamed of having had intercourse with a cross-dressed man, or, specifically, a black man--or all of these? The answer is not clear.

As the Sun stressed of Haslem: "On this occasion, however, the complainant, to recover his money, mustered courage enough to stand the brunt of the trial." What made Haslem unafraid to go public with his accusation? We do not know.

The Verdict

The Herald reported that the jury, "after consulting a few moments, returned a verdict of guilty of grand larceny;' Sewally was sentenced to five years in the state prison.[7]

The Lithograph

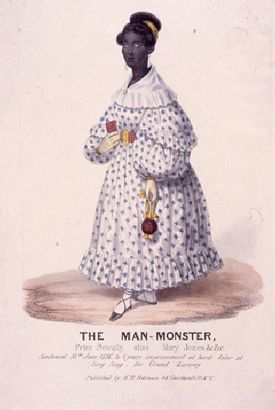

A week or so after Sewallys trial and sentencing a lithograph of him dressed as a woman, and titled" 'The Man-Monster; Peter Sewally, alias Mary Jones;' was published in New York City. Despite the "monster" status invoked by its title, the print portrayed Sewally as a rather ordinary-looking and unthreatening black woman in a clean white dress with small blue flowers. The prosaic, even genteel, image countered his alleged monster status.

The lithograph and newspaper accounts suggested that Sewallys cross-dressing, theft, and sexual conduct were sensational in 1836. But these behaviors were by no means as threatening in 1830s New York as they would have been in, for example, the early 1600s. (See the case of Thomas/Thomasine Hall.)

Years' Later

Nine years later, on August 9,1845, a New York paper, the Commercial Advertiser, reported that "a notorious character, known as Beefsteak Pete, was arrested on Thursday night, perambulating the streets in woman's attire." His object, the newspaper judged, was of a "villainous character." (The name "Beefsteak" apparently defined Sewally by his mode of sustaining the illusion of femaleness during sexual intercourse with men.)

The following year, on February 15, 1846, the New York Herald carried an item about "Pete Sevanley, alias 'beef steak Pete; a notorious black rascal, who dresses in female attire and parades about the street."[8] Liberated from Blackwell's Island on the previous Sunday, this Sevanley had been arrested again for "playing up his old game, sailing along the street in the full rig of a female." He was sent back to prison "to finish some blocks of stone for the next six months."

Interpretation

Sewally's court testimony of 1836 provides us the earliest American evidence of a supportive link between female prostitutes and a man who, at least sometimes, had sex with men. The newspaper reports of that time also documented the judge and jury's response to Sewally. They punished him quite severely for a theft accomplished via a masquerade, and they had a good laugh at his and his white victim's expense. The paper's need to maintain a respectable level of discourse meant that Sewally's sex acts with men were given less explicit coverage than were his cross-dressing and theft.

In these documents, the exact character of Sewally's own desire remains ambiguous, though his pecuniary motive seems clear. But his unusual, defiant, long-term cross-dressing and streetwalking surely suggest a personal proclivity.

His story provides evidence of a man appropriating for his own use a particular model of illicit womanhood, the female prostitute, or "Girls of ill fame." The tales of Peter Sewally and of Sally Binns (discussed in chapter 4 of Love Stories) show that "acting like a woman" was one option available to men in the nineteenth century who, for whatever reason, desired sexual contact with men.[9]

The story of Sewally's arrest and trial also shows us an African-American man working the race, class, sexuality, and gender systems to appropriate for himself a little of the wealth of white men. Did Sewally rob white men, in particular, because they were more likely to carry larger amounts of cash than black men? Or did his robbing of white men also indicate a specifically racial animosity? He certainly suggested, defensively, in his remarkable testimony, that the black community of New York and New Orleans had never found his cross-dressing problematic. White people, he implied, were less tolerant.

Sewally's testimony provides the earliest account of African-American parties in New York City and New Orleans attended, without incident, apparently, by a cross-dressed black man, interested, for whatever reason, in sex with men. Black people accepted Sewally's cross-dressing, and, perhaps even his sex with men, his testimony suggested, hinting at relationships among blacks that varied substantially from those among whites and blacks.

And the white man, Haslem, did he seek a black woman, or a black male cross-dresser, in particular, as a paid sexual partner? Or did he undertake intercourse with Mary Jones just because she was available, whatever her race and whatever her sex? The reports leave many questions unanswered.

Affectionate and sexual, loving or erotic relations between white men and men of color have a long, emotionally fraught American history, as Leslie Fiedler long ago pointed out.[10] Focusing on the intimacy between Mark Twain's Huck Finn and his black friend Jim and the intimacies between white and Indian men in the novels of James Fenimore Cooper, Fiedler analyzed these adventures as fantasies of escape from marriage and manly responsibilities. Such stories were sometimes tales of comradeship and desire--expressing a yearning to reach across the chasm of difference--sometimes tales of conflict and exploitation, as in the case of Sewally and Haslem.

Notes

- ↑ Jonathan Ned Katz, Love Stories: Sex Between Men Before Homosexuality (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), pp. 80-87. Not to be reproduced for commercial purposes without permission from Katz. An earlier version of this account was published by Jonathan Ned Katz in A Queer World: The Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader, Martin B. Duberman, ed. (1997), pages 227-230.

- ↑ See note 18 in Love Stories.

- ↑ See note 19 in Love Stories.

- ↑ See note 20 in Love Stories.

- ↑ See note 21 in Love Stories.

- ↑ See note in Love Stories.

- ↑ See note 23 in Love Stories.

- ↑ See note 24 in Love Stories.

- ↑ See note 25 in Love Stories.

- ↑ See note 26 inLove Stories.

See also: