Postcards: Masculine Women, Feminine Men; early-20th c.

Which is the Rooster, Which is the Hen?

Introduction by Jonathan Ned Katz. Copyright (c) by Jonathan Ned Katz, 2008. Postcards copyright (c) by Marshall Weeks, 2008. All rights reserved.

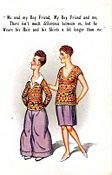

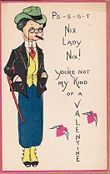

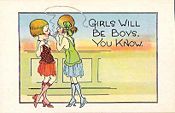

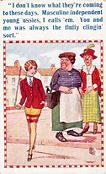

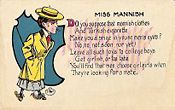

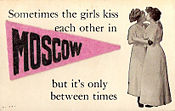

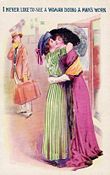

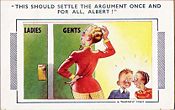

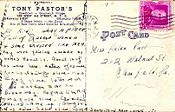

Postcards collected by Marshall Weeks and dating to the early twentieth-century present satirical images of women who wore "mannish" shoes, shirts, collars, ties, and coats, who smoked, went to bars, and who moved independently in the world. Other cards portray effeminate men and, specifically, those then called "fairies" and "pansies."

These popular culture images express the same feeling of threat to ideals of traditional "femininity" and "masculinity" found in that era's medical journal articles and newspaper accounts of gender difference and sexual "abnormality." For how to think about these images historically, please see "Looking at Images" after the postcard display.[1]

An early recording on the same theme as the postcards presents the song "Masculine Women & Feminine Men." The singer asks: "Which is the rooster, which is the hen?"

Click here to play " Masculine Women & Feminine Men" on QueerMusicHeritage.com

This is the recording by Frank Harris (Irving Kaufman) (Columbia 569D, 1/29/26). For a history of the song, see: Edgar Leslie and James V. Monaco: "Masculine Women! Feminine Men!" 1925

For more versions of "Masculine Women & Feminine Men" see: QueerMusicHeritage.com

Click on each postcard for a larger image

Masculine Women and Feminine Men

Masculine Women

Women-Kissing-Women

Feminine Men

Effeminate Male Clerks

On the first of these cards an effeminate male clerk in a dry-goods store fixes his hair and primps while customers go unattended. This man's unmanly vanity and the needs of consumer capitalism are implicitly at odds.

As early as 1860 a parody of Walt Whitman's poem "Song of Myself" attacked the poet by picturing him as a "weak and effeminate" dry-goods salesman or "counter-jumper," an occupation thought suitable for only the most effete of males.[2]

Another document, of 1868 refers to a song titled the "Gay Young Clerk in the Dry Goods Store," by Will S. Hays, a female impersonator.[3] This is one of the earliest documented uses of the word "gay" applied to an effeminate man.[4]

Queer Places

Looking at Images

by Lynley Wheaton. Copyright (c) by Lynley Wheaton, 2008. All rights reserved.

In this digital age, we are often confronted with historical images that are not fully contextualized but can still provide valuable insights into the ways past generations looked at gender and sexuality. Close readings of such images can enhance our understanding of them, and suggest historical research that will clarify their original meanings. Here are some questions to help viewers start thinking about various ways of looking at historical images such as these postcards.

- What could the original purpose of these images be?

- Why are these image grouped together on OutHistory.org? Were the images created by the same person, from the same time period? What clues can the images themselves give us?

- If there is no date on the image, how does one begin to place the image in history? What visual clues are provided that might aid in this process? What outside sources might you use to begin putting these images into a historical context?

- How does fashion contribute to the artist’s intention? What are some of the signifiers that clue the viewer into the artist’s commentary? If fashion expresses ideas rooted in a specific time period, how do these signifiers still function in the present?

- What clues do props and settings add to your reading of the images?

- How does the aesthetic of the image work into your interpretation of it? Your dating of it?

- How do secondary characters work in these images? How does the role of the child work?

- If there is more than one person, what roles are each of the people playing?

- How does the addition of text shift or comment on these images? The use of the rhyme? The repetition of certain ideas (for example, a woman doing a man’s job)?

- In what ways do these images speak to gender? To sexuality? What can that tell us about historical context?

- How does looking at the images in electronic form change the reading? What are the positives and negatives of this experience?

- What have you learned from looking at these images? What questions do they raise about history and the writing of history? How might you use these images in historical research?

Postcards, Gender, Sexuality, History: A Public Forum

References

- ↑ Jonathan Ned Katz is deeply grateful to Marshall Weeks for making electronic copies of these samples from his vast postcard collection and for sharing them with OutHistory.org. For permission to reproduce any of these postcards for commercial purposes, contact Marshall Weeks through OutHistory.org: outhistory@gc.cuny.edu. The introductory text is adapted from Jonathan Ned Katz, Gay/Lesbian Almanac (NY: Harper & Row, 1983), pp. 313-319.

- ↑ Jonathan Ned Katz, Gay American History: Lesbians and Gay Men in the U.S.A. (NY: Crowell, 1976), p. 655 n. 133)

- ↑ Cited on the published sheet music of Hay's "Mistress Jinks of Madison Square," NY: J. I. Peters, 1868, in the collection of Marshal Weeks.

- ↑ Research Request: The earliest documentation of the word gay being used for men who desire sexual contact with men occurs in [?].

<comments />