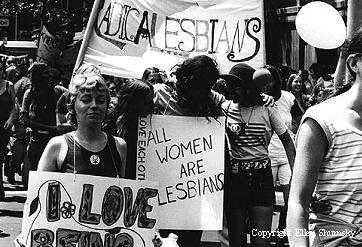

Radicalesbians

This page will focus on Radicalesbians (RL), a group formed in the spring of 1970 by lesbians who had been involved in the Gay Liberation Front and the women’s liberation movement. Radicalesbians was the first lesbian feminist group to emerge after Stonewall.

Origins of Radicalesbians: Sexism in GLF and the First All Women’s Dance

From the beginning, the Gay Liberation Front dedicated itself to combating sexism. Many GLFers believed that sex roles were at the root of their oppression, and a number of men worked hard to develop nonsexist ways of thinking and acting. (Some, such as The Effeminists, eventually dedicated themselves wholly to breaking down “the patriarchy.”) But others continued to act in ways that diminished women’s standing in the group—calling them “girls,” expecting them to make coffee, dominating conversations, and demeaning those who disagreed with them—or questioned how much time and resources should be devoted to so-called “women’s issues.”[1]

Ellen Shumsky, a member of the Gay Liberation Front and Radicalesbians, talks about conflicts between men and women in GLF:

Tensions between men and women came to a head in the spring of 1970, when women proposed hosting their own dances. GLF dances were “overwhelmingly attended by males,” and women had grown weary of “the ‘pack-’em-in’ attitude” of the dance organizers. They longed to create “an ambience that encouraged group dancing and space for conversation.”[2]

While some men supported the women’s efforts to host their own dances, a number of others were opposed to the idea. The group had worked hard to come together across gender lines, and a separate dance seemed not only “‘divisive’ and ‘insulting,’” but also like “‘a step backward.’”[3] What’s more, they argued, women should not be able to use money from the GLF treasury to organize events that barred men.[4]

Despite this resistance, the women prevailed. Their first separate dance--held on April 3, 1970--was “a huge success,” drawing hundreds of women to the space they’d secured at Alternate University. One woman remembered: “We danced fast, we danced slow, we danced Greek-style, we danced in circles and pairs, we rapped, we were stoned on joy. We were all women, all in love with each other, and we had a tremendous sense of power in our self-sufficiency.”[5] The women began preparations for more dances immediately.

The dances not only allowed GLF women to forge a sense of community with other lesbians, but also gave them the opportunity to meet and work separately from men—an experience they found exhilarating.[6]

Later, women in the Aquarius Cell took money from GLF's community center fund to finance independent dances.[7] Their move infuriated many men in GLF, including Jerry Hoose and Michael Lavery, who left the group as a result of their action:

Other Origins: Homophobia in the Women’s Liberation Movement

As GLF women struggled against sexism in the group, lesbians in the women’s liberation movement were battling the anti-gay attitudes of many of their straight sisters. Feminist activism had been empowering for many lesbians, but they also felt alienated by a movement that frequently ignored them or diminished their concerns.

Mainstream groups like the National Organization for Women (NOW) “were openly hostile to lesbians.” NOW president Betty Friedan, for example, was so concerned that lesbians would tarnish the reputation of the women’s movement that she labeled them a “lavender menace.”[8]

Radical women’s liberation groups were more welcoming—and some, such as The Feminists, praised lesbians for their women-centered lives. But too often these groups also wrote off lesbians’ concerns as unimportant or argued that they were dividing the movement.[9]

By early 1970, lesbians from women’s liberation were just as tired as GLF women of “feeling ignored” by the movement they had worked so hard for—and both groups of women welcomed the opportunity to join together in separate Consciousness-Raising groups in the spring.[10]

Karla Jay talks about her experiences with homophobia in the radical women’s liberation group Redstockings:]

The Lavender Menace Action

Shortly after they began meeting in C-R groups, lesbian feminists found their opportunity to challenge homophobia in the women's movement. The NOW-sponsored Second Congress to Unite Women had blatantly ignored lesbianism: “not a single speaker, workshop, or plenary involved an open lesbian.”[11] The newly-united lesbian feminists formed a group to plan an action that would challenge women's liberationists to recognize and embrace their lesbian sisters. They called themselves the Lavender Menace in reference to Freidan’s disparaging comment.

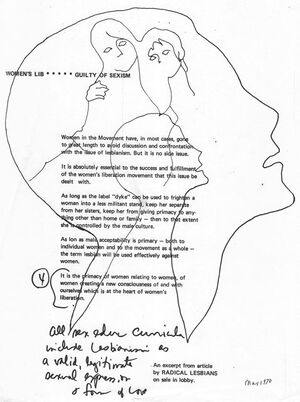

In preparation for the conference, the group wrote the first lesbian feminist manifesto, “The Woman-Identified Woman.” Beginning with the famous assertion that "a lesbian is the rage of all women condensed to the point of explosion,” the document argued that lesbians defied the “limitations and oppression laid on” them by “the female role.” The manifesto challenged women’s liberationists to deal with “this issue,” not only because the movement was inhibited by its anxiety about lesbianism, but also because lesbians’ total commitment to other women put them at the vanguard of the movement.[12]

Ellen Shumsky discusses the “The Woman-Identified Woman”:

On May 1, 1970, about 40 Lavender Menaces infiltrated the Second Congress to Unite Women. At the beginning of a panel discussion that had drawn hundreds of women to the auditorium, the group turned the lights off. When the lights came back on, women wearing Lavender Menace t-shirts had taken over the stage and posters with slogans like TAKE A LESBIAN TO LUNCH, SUPERDYKE LOVES YOU, and THE WOMEN'S LIBERATION MOVEMENT IS A LESBIAN PLOT dotted the walls.[13]

One Menace explained to the audience: “We have come to tell you that we lesbians are being oppressed outside the movement and inside the movement by a sexist attitude. We want to discuss the lesbian issue with you.”[14]

After passing out copies of “The Woman-Identified Woman,” the Menaces began talking about their experiences as lesbians; some of the women in attendance joined them on the stage to do the same. Although a few women walked out, most were receptive to the action.[15]

Karla Jay talks about the Lavender Menace Action:

By the end of the conference, the congress voted to adopt the resolutions laid out by the Lavender Menaces:

- Be it resolved that Women’s Liberation is a lesbian plot.

- Resolved that whenever the label lesbian is used against the movement collectively or against women individually, it is to be affirmed, not denied.

- In all discussions of birth control, homosexuality must be included as a legitimate method of contraception.

- All sex education curricula must include lesbianism as a valid, legitimate form of sexual expression and love.[16]

In the weeks that followed, the Lavender Menaces organized new Consciousness-Raising groups with women from the congress. Soon enough, they decided it was time to form an autonomous organization—and Radicalesbians was born.[17]

Ellen Shumsky talks about the success of the Lavender Menace Action:

Radicalesbians

As Radical Lesbians set out to create their own movement, they worked hard to avoid the problems they had experienced in other groups. They wanted to develop an organization that would nurture each member, encourage equal participation, and discourage patriarchal “leadership hierarchies” that would allow individual women to exert undue influence on the group.[18]

They instituted the lot system so that members took part in all aspects of the organization—from mundane tasks like writing meeting minutes to more challenging jobs like public speaking.[19] With the exception of a general Wednesday night meeting, members met in small groups that encouraged strong bonds and gave all women the opportunity to be heard.[20]

The group aimed to create a supportive community of women, to give lesbians a voice in the gay and women’s liberation movements, and to take action against their oppression. They picketed lesbian bars in an effort to reach out to less political women, contributed to feminist publications like Rat, spoke about lesbianism at colleges and on radio shows, and participated in activities like self-defense classes at an All Women’s Night at Alternate U.[21]

Dissolution

Although Radicalesbians worked hard to bring together a wide range of women, the group nonetheless began to splinter. Women who achieved conventional success were chided for elitism, and less radical members felt alienated by the pressure to conform to radical ways of thinking and acting. In the fall of 1970, Barbara Love left the group to bring back the GLF Women’s Caucus, which she promised would welcome women of all backgrounds and political outlooks.

Members also struggled to create a sense of togetherness in the group. Despite their best efforts to discourage individual members from taking leadership roles, women who were better versed in lesbian feminist theory, were more confident and outgoing, or who had more political experience and organizational expertise nonetheless became unofficial leaders. Less outgoing, less experienced, and newer members often felt diminished or left out.[22]

By 1971, many of the original members had become disenchanted with all forms of organizational activity, leaving the group to focus on transforming their own lives.[23] While RL collapsed within the next year, it helped to spark an explosion of lesbian cultural and political activity that went far beyond the group itself.

Return to Gay Liberation in New York City

Categories

Gay Liberation, Gay Liberation Front, Feminism, Women's Liberation, Radicalesbians, Lavender Menace, Lesbian separatism, New York City

Contact

Lindsay Branson: lindsay.branson@gmail.com

References

- ↑ Karla Jay, Tales of a Lavender Menace (New York: Basic Books, 1999), 82; Martin Duberman, Stonewall (New York: Plume Books, 1993), 247; Toby Marotta, The Politics of Homosexuality (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1981), 238-9.

- ↑ Ellen Shumsky, “The Radicalesbian Story: An Evolution of Consciousness,” in Smash the Church, Smash the State, ed. Tommi Avicolli Mecca (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2009), 190. See also: Suzanne Bevier, “GLF Women Hold First All-Women’s Dance,” Gay Power, Vol. 1, No. 15 (n.d.): 10.

- ↑ Bob Kohler, “Gay Liberation Front-New York,” Gay Power, Vol. 1, No. 15, (n.d.): 10.

- ↑ Jay, Lavender Menace, 126.

- ↑ ”pigmafiapigmafiapigmafia,” Rat, April 17, 1970, unnumbered page. Reprinted in Marotta, Politics, 240.

- ↑ Marotta, Politics, 240.

- ↑ Ibid., 246; Shumsky, "The Radicalesbian Story," 192.

- ↑ Jay, Lavender Menace, 137.

- ↑ Ibid., 138.

- ↑ Ibid., 139.

- ↑ Ibid., 140.

- ↑ Radicalesbians, "The Woman-Identified Woman," in Dear Sisters: Dispatches from the Women's Liberation Movement, eds. Rosalyn Baxandall and Linda Gordon (New York: Basic Books, 2000), 107-8; Marotta, Politics, 241-44.

- ↑ Donn Teal, The Gay Militants (New York: Stein and Day Publishers, 1971), 179.

- ↑ Pat Maxwell, “Lavender Menaces Confront The Congress to United Women,” Gay Power, No. 17, (n.d.). Reprinted in Teal, Gay Militants, 180.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Shumsky, “The Radicalesbian Story,” 192.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., 193.

- ↑ ”Minutes,” August 26, 1970, Radicalesbians Organizational File, Lesbian Herstory Archives, Brooklyn, NY.

- ↑ Ellen Shumsky, personal interview, February 2, 2010; “Meeting Minutes – Radical Lesbians,” September 2, 1970, Radicalesbians Organizational File, Lesbian Herstory Archives.

- ↑ Marotta, Politics, 248-54.

- ↑ Ellen Shumsky wrote that "[t]here was a new realization that Radicalesbians was not a thing but a process, a flow, a way of looking at life from our own centers and trying to live in accordance with that self-knowledge." Shumsky, "The Radicalesbian Story," 195.