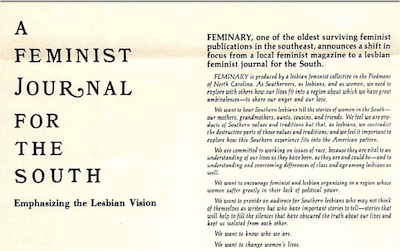

Feminary: A Feminist Journal for the South Emphasizing the Lesbian Vision

This entry is part of: LGBT Identities, Communities, and Resistance in North Carolina, 1945-2012

The feminist and gay rights movements of the 1960s and 1970s fundamentally changed the processes through which lesbians and feminists formed communities, claimed safe spaces for themselves, and challenged the social and political structures they sought to change. The development of a feminist press played a key part in building the Lesbian Feminist Movement and community on a local, regional and national level. Lesbian-feminist newsletters and newspapers such as Radicalesbians, created nuclei around which feminists and lesbians were able to form communities of women united by their sexual and political identities, and the vision of producing vehicles for academic and political discussion that were created, controlled and used by women. As the feminist movement gained momentum, so did the desire to manifest it in a tangible print media and thereby create and control the identity and the representations of the feminist and lesbian-feminist movements; it was from this environment that The Research Triangle Women’s Liberation Newsletter, predecessor of what would one day become Feminary, was born.

The first issue of The Research Triangle Women’s Liberation Newsletter was published on August 11, 1969 by a group of feminists based in the Chapel Hill and Durham community, the majority of whom were graduate students at UNC participating in various feminist discussion and activism groups. [1] The newsletter had the stated intention of “communicating the interests of [these] different groups to other groups”. [2] As Jennifer Gilbert described it in her Master’s thesis, "Feminary of Durham-Chapel Hill: Building Community Through Feminist Press", “the newsletter announced itself as a voice of unity for reporting diversity.”[3] With the publication of the third issue in October of 1969, it gained a new appellation of the Female Liberation Newsletter of Durham-Chapel Hill and it continued to emphasize the breadth of different feminist groups in the Triangle, with a specific focus on issues surrounding working class women. The newsletter was intended to be published weekly, and sold at five cents an issue and editorial positions for each issue were to rotate among the different groups involved in its production. The editorial position ended up falling almost exclusively to Elizabeth Knowlton and Marguerite Beardlsley, who after calling repeatedly for help in putting together the newsletter, were eventually forced to stop publishing it in 1971.[3] In the issues published in 1971 there were several brief mentions of lesbian literature and issues pertaining to lesbians. Although these mentions were sporadic it is worth noting because of the future direction of the newsletter.

In 1973 Elizabeth Knolten, Leslie Brogan, Nancy Blood and Leslie Kahn moved into a house in Chapel Hill together, thereby forming the nucleus of the first “lesbian-feminist commune in the area.”[3] These women formed a close-knit community and together they decided to revive the newsletter, which they named The Feminist Newsletter, the first issue of which was released in February of 1973.[3] This new publication ceased to be merely an announcement sheet for local feminist groups; it was a bi-weekly publication made up of essays, poetry, local and regional news, announcements, book and movie reviews, and classified adds. The collective which ran the publication of the newsletter repeatedly invited women in the Durham and Chapel Hill area to contribute to its creation. This continuous dialogue between the collective and its readership as well as its concerted emphasis on local and regional issues embodies the relationship the newsletter had with the national feminist movement of the time.[3] Through the Newsletter, the collective helped to describe and define issues important to the regional feminist community.

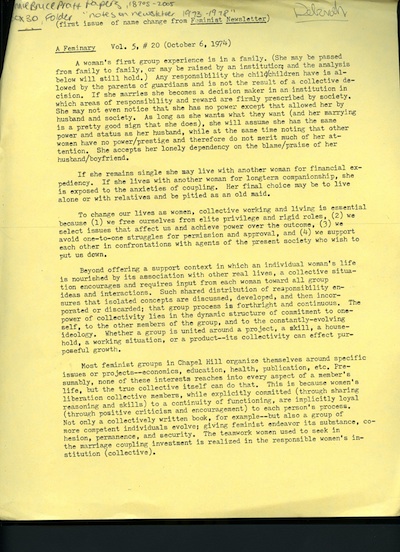

Unlike its predecessor, The Feminist Newsletter attempted to address the subject of lesbian-feminism and issues surrounding lesbians within the larger feminist movement. The members of the collective producing the newsletter were self-identified lesbian-feminists, thus lesbianism figured prominently into the newsletter, although the early issues were not self-consciously directed towards lesbians. The appearance of lesbian-related issues increased when in the fall of 1973 they began to partner with the Triangle Area Lesbian-Feminists (TALF), which was formerly known as the Lesbian Rap Group.[3] In the March issue of 1974, the collective published a newsletter which was entirely dedicated to the lesbian-feminist community. This issue featured articles about lesbian activities in the Triangle, a review of a lesbian music group and a lesbian novel, and its central essay was “The Politics of Lesbianism – Chapel Hill.”[4] This issue represents a turning point in the newsletter, which began to put an increased emphasis on lesbian-feminist issues. In October of 1974 the newsletter gained a new name: Feminary. Its new appellation was done “because although it had originated as a newsletter it now had the scope of a journal.”[3]

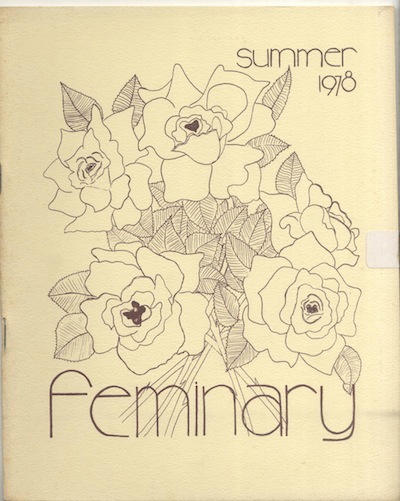

An issue of salient importance to the collective producing Feminary was that of “collectivity” and their desire to create, publish and interact in a manner that was egalitarian and non-hierarchal. This dynamic spirit of radical egalitarianism was characteristic of feminist organizations of the time. [5] Throughout the year of 1975 the collective that produced Feminary debated the idea of separatism, meaning focusing specifically on lesbian-feminist issues. Some members felt that Lesbian-Feminist issues were often not given precedence in the feminist movement, in the ways that straight-feminist issues were, yet the collective decided not to declare that they were an exclusively lesbian publication out of a fear that they might ostracize their straight readers.[3] The publication continued to put an emphasis on lesbian-related issues while still maintaining its appeal to larger audiences until 1978, when it issued a statement that from then on Feminary would focus exclusively on lesbian-feminist issues and the lesbian community. At this point the journal, which was now called Feminary: a Feminist Journal for the South Emphasizing the Lesbian Vision, was being produced seasonally and the core of the collective publishing it was comprised of Minnie Bruce Pratt, her lover Cris South, Mab Segrest, and Susan Ballinger. [6]

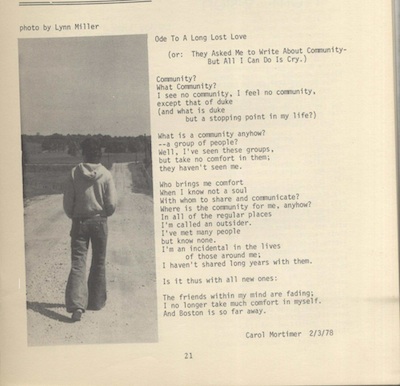

Focusing primarily on lesbian issues provided the collective with a needed cohesion and allowed them to be free to change directions and grow to fulfill their vision of producing poetry, personal essays, art, interviews, news, and book reviews of lesbian women in the South. This shift in focus was met with a tangible response and the collective was flooded with submissions from community members.[3] The collective also begin to place a much greater emphasis on the actual process of producing the journal and of forging an identity through it, and this in fact took precedence over printing the issues on time. According to Mab Segrest, “I had a very strong sense that we would be filling a need in ourselves. To understand what it was to be lesbian… given the resonance of questions of Southern identity which had denied lesbians openly”[7] The collective understood their work as something that helped to build community, stating, “There was a strong function that lesbian writing served in creating lesbian consciousness and lesbian community…. We were a crucible for sorting through questions of identity…”[8]

This new direction, however, was not to the liking to all of the members involved with Feminary before it was transformed into a literary journal; some members of the collective felt that the group dynamic had been altered in such a way that it was almost entirely dominated by the core group, who were all writers, and two of whom had Ph.D.’s.[9] The collective’s meeting were increasingly dominated by a few members, something which Sherry Kinlaw described as “the tyranny of the P.h.D’s”.[10] This is a marked shift from the egalitarian model that the collective had hitherto emphasized. The collective producing the journal began to fragment and the number of issues being published began to sharply decline, with only three issues being released between 1980 and 1981.

The last issue of Feminary was released in Spring of 1982. The final collective members were enumerated as Eleanor Holland, Helen, a graphic designer, Minnie Bruce Pratt, Mab Segrest, and Cris South.[11] Minnie Bruce Pratt and Cris South broke up and Minnie Bruce moved to Washington D.C. and Eleanor and Helen followed her there, leaving only Mab Segrest to publish the journal.[3] Before leaving North Carolina, the remaining collective members placed classified adds in various women’s journals across the country to see if another group would be willing to take over publishing Feminary.[3] They received two responses: one from an all-white collective in Atlanta and another from a multi-racial group based out of San Francisco.[3] The collective decided to move the journal to San Francisco because that group there seemed “more consistent with what we hoped to do with the magazine.”[12] The new magazine described itself as a “national magazine with an international perspective, a magazine of lesbian feminist politics, passion and hope”; sadly only two issues were ever published, before Feminary died out all together.[13]

- ↑ Research Triangle Women’s Liberation Newsletter, Vol. 1, Issue #1, Aug. 11, 1969

- ↑ Research Triangle Women’s Liberation Newsletter, Vol. 1, Issue #2, Oct. 12, 1969

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 Gilbert, Jennifer. "Feminary" of Durham-Chapel Hill: Building Community Through Feminist Press. MA thesis. Durham: Duke University, 1993. Print.

- ↑ The Feminist Newsletter, Vol. 5, Issue #6, Mar. 24, 1974

- ↑ Sara Evans, Personal Politics: The Roots of Women’s Liberation in the Civil Rights Movement and the New Left (New York: Random House, 1979), 222.

- ↑ Feminary Vol. 9, Issue #1, Spring 1978

- ↑ Mab Segrest, interview by Jennifer Gilbert, 11 February 1993, Durham, North Carolina, tape recording.

- ↑ Mab Segrest, interview by Jennifer Gilbert, 11 February 1993, Durham, North Carolina, tape recording.

- ↑ Sherry Kinlaw, interview by Jennifer Gilbert, 15 November 1992, Durham, North Carolina, tape recording.

- ↑ Sherry Kinlaw, interview by Jennifer Gilbert, 15 November 1992, Durham, North Carolina, tape recording.

- ↑ Feminary Vol. 12, Issue 1, Spring 1982.

- ↑ Mab Segrest, interview by Jennifer Gilbert, 11 February 1993, Durham, North Carolina, tape recording.

- ↑ Feminary, Vol, 1, Issue #1, 1985.