Minnie Bruce Pratt, 1946 - present

This entry is part of: LGBT Identities, Communities, and Resistance in North Carolina, 1945-2012

Introduction

Minnie Bruce Pratt is a lesbian, feminist, activist, teacher, poet, mother, and partner. Born and raised in Alabama, she moved to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, and received her Ph.D. in English Literature in 1979.[1] Pratt is well-known for her feminist activism in North Carolina in the 70s and 80s with lesbian feminist periodical A Feminary and her work with the National Organization of Women. She has published six books of poetry and received numerous awards for her work. Currently, Pratt lives in New Jersey with her partner, transgender activist Leslie Feinberg.

Early Life

On September 12, 1946, Minnie Bruce Pratt was born in Selma, Alabama. She attended the University of Alabama where she met and married her former husband, Marvin E. Weaver II. Her marriage was, in some ways, an “act of rebellion”[2] against the life her family had pushed her into, such as university and sorority life. Her first pregnancy of her son Ransom put a strain on their relationship. Pratt found solace in the “collective houses” in Chapel Hill, where women were living together and organizing in Chapel Hill. It was her first exposure to the “women’s lib” movement of the 1970s.

Loss of Custody and Crime Against Nature

In 1975, Pratt left her husband to live as a lesbian and subsequently lost custody of her two sons under North Carolina’s “Crime Against Nature” law. The law is classified under “Offenses Against Public Morality and Decency” and is still in place today, despite the passing of Lawrence v. Texas case which made sodomy laws unconstitutional. The law states that “If any person shall commit the crime against nature, with mankind or beast, he shall be punished as a Class I felon.“[3]

At the time, Pratt knew that coming out and living openly as a lesbian was a risk. But living in an unhealthy marriage and repressing her queer desires was too emotionally damaging for her to continue.

“[I]t was, you know, when the right wingers say, Oh, we can’t let these lesbians and these feminists, these women’s libbers, you know, we can’t let them have access to our children, we can’t let these ideasget out — well, of course, they’re right, they’re correct. Once we know that there are other ways to live, sometimes you will choose to live these other ways. I mean, I could have repressed myself. I could have chosen differently. It would’ve been spiritual suicide. I said to myself at the time, “If I don’t do this, if I don’t act on this emotion and this erotic feeling, I will be committing spiritual suicide.” But I could’ve chosen that. I knew I was going to lose my children. I knew it was going to happen. I mean, on some level, I knew.”[2]

Under the divorce settlement, Pratt was not allowed to see her sons in her own home if she lived with any other person. In order to see them, she drove twenty-eight hours total on three-day weekends.[4] Losing custody under the “Crime Against Nature” law declared that Pratt was unfit to parent at all, and thus the instances in which she got to see her sons was dictated mostly by her husband and his lawyer.

In 1989, Pratt published a collection of poetry titled Crime Against Nature. The book is a powerful and emotional journey into her personal life and struggles after losing custody of her children. It was the Lamont Poetry Selection of 1989. The experience of loss and grief shaped her morality and led her to a life of activism for women’s rights and specifically lesbian rights.

Feminary

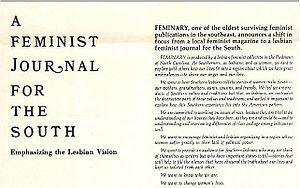

From 1977 to 1982, Pratt worked with a feminist collective in Durham to create the lesbian feminist periodical Feminary: A Feminist Journal for the South Emphasizing the Lesbian Vision. In its early years, Feminary was simply a feminist periodical, but it was not selling. As an experiment, the collective did an issue that focused on lesbian issues, and it sold much better than previous issues. The collective decided to change Feminary to Feminary: A Feminist Magazine for the South Emphasizing Lesbian Issues. Pratt joined right the collective when this change was made. The other members of the collective were Mab Segrest, Susan Ballinger, Helen Langa, Eleanor Holland, Cris South, Aida Wakil, and Raymina Mays.

Based in Durham, NC, the women of Feminary, including Pratt, focused on issues of what would later be coined as “intersectionality.” The magazine featured essays, poetry, and art by lesbians of the south, and touched on issues of class and race and regional identity throughout. Pratt contributed essays, such as an instructional piece teaching women how to organize phone-banking and canvassing in support of the never-passed Equal Rights Amendment, and poetry about her own life and experiences as a lesbian feminist in the south.

In 1982, Pratt moved to Washington D.C. from Durham, thus leaving the Feminary collective. The magazine continued publishing until 1985.

Later Life and Activist Work

While living in Washington D.C. in the 1980s, Pratt continued organizational work for women’s rights and lesbian rights while also developing her identity as a writer. Pratt met her partner, Leslie Feinberg, in 1992 at a conference focusing on transgender liberation and its relation to the feminist movement. After the conference, Pratt and Feinberg began corresponding. Pratt moved to Jersey City and continued organizing with the Workers World Party and getting involved with “red feminism”.[2] She shifted away from the identity of “feminist” because of its second-wave connotation, and embraced the Workers World Party due to its inclusivity and support of women’s, transgender, and queer liberation, as well as its antiracist and anti-imperialist stance. Currently, Pratt works with the International Action Center, and is the Professor of Women’s & Gender Studies as well as Writing & Rhetoric at Syracuse University.

Published Works

The Sound Of One Fork. 1981.

Yours In Struggle: Three Feminist Perspectives On Anti-Semitism And Racism. 1984.

We Say We Love Each Other. 1985.

Crime Against Nature. 1989.

Rebellion: Essays 1980-1991. 1991.

S/HE. 1995.

Walking Back Up Depot Street: Poems. 1999.

The Money Machine: Selected Poems. 2003.

The Dirt She Ate: Selected and New Poems. 2003.

For more of Pratt’s writing, selections can be found on her website.

Notes

- ↑ “Minnie Bruce Pratt Biography,” last modified June 25, 2010, http://www.mbpratt.org/bio.html

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Minnie Bruce Pratt, interviewed by Kelly Anderson, Voices of Feminism Oral History Project, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, March 16-17, 2005.

- ↑ North Carolina General Statutes, 14-177.

- ↑ Minnie Bruce Pratt, “One Good Mother to Another: Lesbian Mothers Fight for Custody of Children,” The Progressive, November 1993, accessed April 19, 2012, http://www.glapn.org/sodomylaws/usa/virginia/vanews25.htm.

- ↑ http://sites.duke.edu/docst110s_01_s2011_bec15/print-culture/feminary-newsletter/

written by Kathleen Jones